Embroidered sampler made at the Female Association Quaker School by Charlotte Gardner for Mary M. Perkins, a member of the Female Association, 1813, Metropolitan Museum of Art

HIDDEN VOICES: HOW WOMEN’S NEEDLECRAFT CONTRIBUTED TO THE ABOLITIONIST (AND FREE SCHOOL) MOVEMENTS

By Ellen M. Spindler, Bowne House Collection Volunteer with research assistance provided by Kate Lynch and Charlotte Jackson, Bowne House Archivist

Friends’ (Quaker) settlements were among the early participants in abolitionist and anti-slavery activities, including the Underground Railroad network, as we described in a previously published article on the Bowne House website, “Eight Years of Documented Bowne House Residents’ Involvement in a Network of the New York Underground Railroad from 1842-1850.” At its yearly meeting in 1768, the Flushing Meeting record reflects adoption of a committee report that "Negroes were by nature born free and when the way opens liberty ought to be extended to them..." [ii] The New York Meeting finally issued a resolution in 1776 to ban the acceptance of contributions and services from those members who held slaves; thereafter, those members were disowned. [iii] By 1787, the New York Yearly Meeting certified that none of its members held slaves. [iv] Quakers’ early decision to manumit the persons they or their ancestors had enslaved, even before they were freed by operation of law, thus constituted the first wave of abolition in New York and other neighboring states such as Pennsylvania.

These Quaker actions helped to create one of the earliest free black communities in the greater New York City area in Flushing where many Quakers lived, even before the consolidation of Queens into New York City in the late 19th century. [v] The African Methodist Society, comprised of Native Americans and free blacks, is believed to have been formed there in the late 1700s, meeting in private homes; the Macedonia A.M.E. church in Flushing first purchased land there in 1811. [vi] This mixed-race community (referred to by some as “Black Dublin”) was thus likely formed even before the better-preserved and still occupied Sandy Ground community established in Staten Island in 1828, [vii] the Weeksville neighborhood in Brooklyn established in 1838, [viii] and the (now destroyed) Seneca Village established in Manhattan in 1825. [ix]

Certain New York Quaker women (including Bowne and Parsons women) devoted their time and energy to the 19th century Free School movement which consequently arose in the early 1800s to provide an education to children in these communities of both enslaved and formerly enslaved African-Americans. Concurrently they contributed to the second wave Abolitionist effort to free the remaining enslaved in New York, first with the Act for Gradual Abolition in 1799, [x] and then with the 1817 Act Relative to Slaves and Servants (Final Emancipation Act), which set a date for their full emancipation by July 4, 1827. [xi] Finally, many of these women aided the broader third wave Abolitionist and anti-slavery movement which arose in the 1830s through the 1850s to help enslaved African-Americans escape from the South and aid free blacks in the North otherwise at risk.

Early Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle Gatherings

In the early to mid-1800s, local sewing circles often provided women with exposure to anti-slavery literature and resolve. [xii] The women involved in these circles had an extreme devotion to them and many were Friends in the greater New York City area, as well as in upstate New York. Some believe Quaker participation in both the Abolitionist and Free School movements came from a central tenant of their religion: that there is a universal “Inner Light” accessible to all, which prompts a concern for human suffering and injustice and an imperative for humanitarian action to treat every person equally as an expression of God’s universal love. [xiii] This was true for both the more evangelical and Orthodox Friends like the Bownes and Parsons residing in the Bowne House, who relied on guidance from the scriptures as well as the “Inner Light,” and for the more “quietist” branch of the Friends community, who focused primarily on revelation from within.

Arising out of this religious philosophy, Quaker women’s needlecraft both directly and indirectly contributed to the 19th century Free School and Abolitionist movements. Many of the Quaker women in New York at this time who were involved in group needlecraft activities, such as sewing samplers, quilts, or other hand-sewn objects, believed that there was a moral duty to provide African-Americans with a free education, as well as their freedom. Their efforts directly challenged the false narrative of proponents of slavery that African-Americans were not capable of, or worthy of, an education to provide them with an equal footing in society, as well as similar views about women, including African-American girls and women.

Anti-Slavery Samplers at the African Free Schools

The initial model for these Quaker women was a charity school previously established in New York City, the African Free School (AFS). The AFS was initially founded in 1787 by members of the New York Manumission Society, which included Quakers such as Robert Bowne and Catharine Bowne’s husband John Murray, Jr., to provide an education to both male and female children of the enslaved and formerly enslaved. By the time New York entirely abolished slavery in 1827, there were seven African Free Schools, five of which employed black instructors. [xiv] Needlework, including the sewing of samplers, was added to the AFS girls’ curriculum in 1791, in addition to reading, writing and arithmetic.[xv] The African Free Schools operated until 1835 when they were absorbed into the Public-School Society (PSS), the successor to the Free School Society (FSS) charity schools for boys, which were commenced after the charity schools earlier established by Quaker women. [xvi]

There are only two AFS samplers known to have surfaced to date. [xvii] At the time Rosena Disery (1805-1877) crafted this sampler at the AFS, she would have known that, under New York’s 1799 Gradual Abolition Law, even if she was born free, other African-American girls and women would only gain their actual freedom at age 25 or by July 4, 1827. [xviii] As explained by Margi Hofer, Director of the New York Historical Society, in the Curator Confidential video presentation “Truth Revealed,” the sampler contains the final stanza of a poem titled “Self-Love and Truth Incompatible.” It was written by French female mystic Madame Jeanne-Marie Guyon, published in England in 1779 by poet and anti-slavery advocate William Cowper, and later reprinted in the United States in the early 19th century.[xix]

The other sampler was made at an AFS school by Mary Emiston in 1803, and even more explicitly refers to slavery and freedom: “In Christ Jesus there is neither bond nor free that He came to let the oppressed go free and to break every yoke ... Blest be the men who taught the heavenly art To break slav’ry’s bonds from freedom’s plains...” These two samplers show us that girls at the AFS schools were either permitted or required to make samplers with implicit or explicit anti-slavery content. Even if required, this gave girls a chance to express their identity in sewn objects, a rare opportunity for black female artisans at the time.

Samplers, writings, and other works of the AFS students were often displayed at the schools on Examination Day at the end of the school year, providing an opportunity for wider dissemination of the anti-slavery views and voices expressed by the chosen verses as a hand-sewn artistic contribution to the Abolitionist Movement.

The New York Female Association Schools and Samplers

Around the turn the of 19th century, the Association of Women Friends for the Relief of the Poor, which later became known as the New York “Female Association” (FA), established what became an antecedent to the New York City public schools, operating four Manhattan schools from approximately 1801 until 1845. [xxi] Hannah Bowne, one of Robert Bowne’s daughters, was among the women on the committee appointed by the FA in 1801 to establish its first school. Originally co-educational but soon admitting only females, the FA schools were open to children of poor parents who did not belong to any “religious society.” These schools were a prototype combining elements of private, independent, parochial, and public schools. [xxii] The FA incorporated in 1813 and was eligible to receive money from the State Common School Fund until 1828, when it became reliant on contributions and subscriptions. [xxiii] The FA girls’ schools were absorbed by a newly formed Board of Education in 1845. [xxiv]

Both the FA schools, and those of a later established “Flushing Female Association” (FFA), included needlework in their curricula. According to Betty Ring, “a charming group of small samplers has survived from several New York City schools operated by Quaker women.” They are very finely worked, notably made by girls from the poor working class. [xxv] Most of the Female Association’s samplers were made as gifts for the Quaker ladies who served as benefactors or members to acknowledge their membership and subscriptions or donations. [xxvi] These FA and FFA samplers share overall characteristics of composition and stitching, as does the Disery one made at the AFS, which also was established and influenced largely by Quakers. These characteristics include the inclusion of verses more than alphabets, often with a title, a balanced composition with small stitched motifs, and black lettering with a crisp Roman block font. [xxvii]

One of the Manhattan FA samplers was made by Lucy Turpen in 1815 for Robert Bowne’s daughter, Jane Bowne Haines (c.1792-1843), at the FA School No. 3 in Manhattan. School No. 2 was opened in 1815 in a designated room within the FSS/PSS boys’ school on Henry Street; the location of School No.3 is not yet known. [xxviii] Lucy Turpen later taught at the African Free School and was hired to resurrect their needlework curriculum, [xxix] where she became a highly esteemed teacher. Jane Bowne Haines, a member of the FA, was a well-known Quaker horticulturalist. After her marriage to Ruben Haines III, she resided at Wyck House, a historic Quaker house in Germantown, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia.

Jane’s father, Robert Bowne, of course, was not only the founder of Bowne Printing & Co., but one of the founders of the New York Manumission Society and a trustee of the African Free School. It is not surprising that his children were raised with the same benevolent and abolitionist beliefs. Jane is also believed to have been sympathetic to abolitionist beliefs for a variety of other reasons: she attended the co-educational Quaker Nine Partners Boarding school in New York, which taught anti- slavery values, and she and her husband Ruben Haines III socialized with Lucretia Mott and her husband (both of whom had attended Nine Partners with her). [xxx] The Wyck House has an 1838 report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (founded by Lucretia Mott), suggesting Jane may have been a member. A distant Haines cousin, John Johnson, had a house two blocks away from the Wyck House which has been documented as a stop on the Underground Railroad. [xxxi]

Lucy Turpen sampler for Jane Bowne Haines, a member of the Female Association, 1815, courtesy of the Wyck Association

Another sampler with shared characteristics (likely from a private Quaker school or Manhattan sewing circle) was made by Anna Bowne, one of Robert Bowne’s granddaughters, in 1831 when she was eight years old.

Anna Bowne sampler, 1831, private collection. Photo credit: M. Finkel & Daughter

The Flushing Female Association School and Samplers

Soon after formation of the FA, women from the Bowne House and the greater Flushing Quaker community established their own “Flushing Female Association” (FFA) in 1814. It provided an education to a poor and interracial group of co-educational students both before and after slavery was finally abolished in New York. [xxxii] Two of the original founders of the FFA were Bowne House residents Ann Bowne (1785-1863) and Catharine Bowne (1789-1830); original 1814 subscribers included Hannah Bowne, Isaac Bowne, Flushing’s postmaster, and Samuel Parsons, a Quaker minister and husband of Mary Bowne Parsons. Other family members, such as future New York City mayor Walter Bowne, are listed as “donors.” [xxxiii]

Other Bowne and Parsons women and relatives who later became members and officers, or who were noted as “those particularly interested in the work,” included Mary (Bowne) Parsons (1784-1839), admitted in 1819; Eliza R. Bowne, her sister; Susan H. Parsons (1824-54), her daughter-in law; her daughter, Mary B. Parsons (1813-1878); and granddaughter Anna Parsons (1869-1948). Also included in FFA membership rolls are relatives of Samuel B. Parson’s wife Susan (Howland) Parsons: namely, Louisa Howland and daughter, and Anabella Howland (Leavitt). [xxxiv]

The FFA regularly met at the Bowne House, [xxxv] where Mary Parsons’ husband, Samuel Parsons, safeguarded their funds. The FFA had a sampler sewing circle among themselves, [xxxvi] as well as in their schools. [xxxvii] We are investigating to what extent this needlework may have contributed to anti-slavery fairs, provided quilts or other necessities for freedom seekers or needy free blacks, or at the very least, assisted in fund-raising for their educational endeavors for the African-American community. The 1821 FFA minutes show that Mary (Bowne) Parsons was scheduled to visit the FFA school that year as an overseer, the same year that the sampler shown below was made for her by Abigail Smith (admitted 1818). [xxxviii]

Abigail Smith sampler for Mary (Bowne) Parsons as member of FFA, 1821, private collection. Photo credit: M. Finkel & Daughter [xxxix]

Initially, the FFA school was racially integrated (“without a color line”) and open to all who had insufficient means for a private education. It operated in premises with rent paid to Hannah Bowne until 1821, when a one-story wooden schoolhouse was built on two lots purchased on Liberty Street (later Lincoln Avenue, now 38th Avenue) between Main and Union Streets in Flushing. [xl] After about 1838, the Association served solely African-American students, and began receiving public funds sometime after Flushing opened segregated public schools. [xli] At that time, the Association received two of its largest gifts, including one fund established by a Quaker donor named Matthew Franklin for the schooling of poor African-American children whose parents had been held in slavery by Quakers. FFA accounting records indicate that Samuel Parsons also made a $950 donation in 1840 to establish a permanent fund. [xlii] A new brick school was built in 1862 and opened near the old one, [xliii] although the school was temporarily closed after the draft riots in 1863.

Flushing Female Association School, Southside Lincoln Ave. bet. Main and Union St. Flushing, 1922, Queens Digital Library

After the Board of Education rented the new school building, the Association offered extracurricular activities for the students, established the Flushing Colored Mission Sunday School, which ran from at least 1866-1910; and provided financial scholarships for African-American students. Later, after 1887, the FFA took back the building and used it as the headquarters of a “Colored Helping Association.” [xliv] The FFA schools thus had a different focus in helping both girls and boys in the African-American community, as compared to other earlier New York FA schools which primarily focused on girls’ education. Sadly, the historic FFA school near Union Street in Flushing was later demolished; the site is now included as part of the Flushing Freedom Mile.

Nine Partners Boarding School and Sampler

Private Quaker co-educational schools which taught needlecraft to girls, among other subjects, also helped to provide important connections which later proved useful in the Abolitionist movement. One of the older samplers in the Bowne House collection was made by Eliza Bowne (1787-1852), aunt of the three sons of Samuel Parsons known to have later become agents of the Underground Railroad. Eliza attended the Quaker Nine Partners Boarding school in Dutchess County, one of the first co-educational boarding schools in the country, located in what is now Millbrook, just twenty miles north of Quaker Hill near Pawling.

Eliza Bowne’s sampler from Nine Partners Boarding School, 1800, Bowne House Collection

Historian Fergus M. Bordewich has described Nine Partners and the adjacent Meeting House as “the most important single abolitionist institution in the valley—and one of the most important in the country,” adding “it may have served as a sort of command center for the underground in the entire region.” [xlv] He added that it was a school that taught the evils of slavery among other Quaker values; for example, “as early as the 1810s, students were required to memorize a lengthy anti-slavery catechism that described slavery as a dreadful evil.” It stated that ending slavery was “a great revolution” and a “noble purpose” for which men and women had been created by their Heavenly Father. [xlvi] The adjacent Meeting House was constructed in 1780 and is still existing.

Drawing of Nine Partners Boarding School, 1816, unknown artist, courtesy of Oakwood Friends School

Nine Partners was founded in 1796 by Joseph Talcott, among others; Talcott was a Quaker whom we know received a letter in 1834 from Eliza’s brother-in-law, Samuel Parsons, who was married to Eliza’s sister Mary Bowne Parsons. [xlvii] This correspondence discussed Samuel’s involvement as Clerk of the New York Meeting in raising $1000 to move free Southern blacks threatened with a return to slavery further north. [xlviii] Eliza, whom may have been in one of the first classes of Nine Partners Boarding school, had already made samplers as a student there in both 1800 (at age 12) and 1801. Her attendance and Samuel’s later correspondence with Talcott are not surprising, as her uncle, Robert Bowne, Samuel’s father, James Parsons, and John Murray, Jr., another relative, were all appointed on the initial Committee of the New York Meeting convened in 1795 to consider the proposed idea of the Boarding School. [xlix] Once approved, the New York Meeting later continued to supervise the Nine Partners Boarding School. [l]

One of Nine Partners most well-known alumna was Lucretia Coffin Mott. Lucretia Coffin Mott attended the school in 1806 at age 13 and graduated in 1810, so she likely did not overlap with Eliza Bowne, but many of its students embarked on lives as abolitionists and women’s suffrage campaigners, grounded in New Partners’ values and education. As previously mentioned, Jane Bowne Haines, Eliza’s cousin, attended the school from 1809-1812, so she did overlap with Lucretia Mott, who stayed on as a teaching assistant until 1811. One possible fellow student attending with Eliza might have been Hannah Sutton, who was born in 1787 (the same year as Eliza) and who later married the staunch abolitionist, Joseph Pierce. [li] The home of their son and daughter-in-law Moses and Esther Pierce in Pleasantville, New York has been documented as an Underground Railroad station. Thus, Quaker schools became an important place for girls to make lifelong contacts in abolitionist circles.

Anti-Slavery Fairs

What started out as small female sewing circles, eventually grew into larger fairs, including Christmas fairs and world fairs, serving from the 1830s through the 1850s as an innovative source of fund-raising by female anti-slavery activists [lii] during the third wave of the Abolitionist movement. Quakers and other denominations turned their focus to raising funds and hiring agents to help free the enslaved in the South and aid free blacks still at risk in the North.

We know about these fairs not only from extant posters, broadsides and written newspaper articles and announcements, but also from the private letters of these female activists. An anti-slavery message was spread to the attendees alongside the selling of baked goods, clothing items, luxury and common household items, sometimes sourced internationally, that all contributed to the cause. [liii] This provided an opportunity for the convergence of domestic and political activities for abolitionist women who could then work alongside men and put their needlecraft to a benevolent charitable use. [liv] As fairs became larger, they moved from homes and churches into hotels, stores, and meeting halls. [lv] Some of the sewn objects were explicit in their anti-slavery message.

For example, African-American black dolls crafted by black female artisans were at times sold to protest the institution of slavery and white abolitionist women purchased them to raise money for the cause or to give them to their children to demonstrate more humane play. [lvi] In a video, Crafting Black Dolls, discussing a recent New York Historical Society exhibit “Black Dolls,” one commentator noted an expression used by abolitionists: “may our needles prick the slave holder’s conscience.” [lvii] The Bowne House has one 19th century African-American black doll in its collection and is investigating its provenance to see if it might have been made for such a fair.

African-American Black Doll, Bowne House Collection

A recent exhibition at the Sharon, Connecticut Historical Society of “The Sampler Collection of Alexandra Peters (Girls Stitching History)” included items identified as made for Anti-Slavery fairs: one is a potholder by an unknown maker circa 1830-50 embroidered “Any holder but A Slaveholder.” The Sharon Historical Society states that, before adding a sampler to her collection, Alexandra Peters “researched the lives of the sampler makers and the world revealed by their needlework. The girls in this collection were touched by abolition, the Underground Railroad, and the anti-slavery movement.” [lviii]

Photo credit for potholder: Alexandra Peters

Another example is a quilt, recently on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition In America: An Anthology of Fashion, that was displayed at the New York 1853 Exhibition of All Nations by fashion retailer M.T. Hollander. The quilt has thirty-one embroidered stars representing the states in the United States at the time, encircling a portrait of George Washington and a poem admonishing him for furthering the institution of slavery, “a monstrous hideous blot.” The museum label for this quilt states “Needlework, often sold at antislavery fairs, was one of the key ways that women participated in the abolitionist movement.” Hollander’s papers indicate that she was engaged with social justice issues. She purchased this quilt, or at least a portion, of it from a woman who won a medal at the 1851 London Crystal Palace Exhibition.

Possibly Maria Theresa Baldwin Hollander, Abolition quilt, ca. 1853, displayed by her at 1853 Exhibition of All Nations (World’s Fair) in New York, courtesy of Historic New England

Boston and Philadelphia sponsored some of the first anti-slavery sales in 1834 and 1836; they appear to have been the largest and most frequent ones held. [lix] Rochester, New York has also been identified as having more established fairs. [lx] Smaller circles or fairs were encouraged to donate and sell items at the larger fairs in places like Boston and Philadelphia which helped to advertise the anti-slavery message; this, in turn, aided smaller fairs rise among the Northeast and Midwest. For example, a broadside for the Eleventh Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Fair to be held in 1844 stated “We entreat whomever this sheet reaches instantly to announce an intention of aiding the ELEVENTH MASSACHUSETTS ANTI-SLAVERY FAIR, and to form, if possible, a little circle for weekly anti-slavery effort throughout the year.” [lxi]

Although women were heavily involved in abolitionist activities, opinion was divided as to their proper role. Some people believed that women should serve in auxiliary roles that did not expose them to competition with men. However, other women played a highly visible role as writers and speakers for the cause; some of them gained activist experience that they later used in support of women’s rights. For example, a Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was organized in 1833 [lxii] and, in one circular, they advertised a fundraising event to support an agent of the Massachusetts Society, inviting all towns to take a table at their fair. [lxiii]

The larger urban fairs were profitable fundraisers. For example, the 1843 Anti-Slavery Boston fair raised $2800. [lxiv] The 1847 Boston fair raised a stunning $3854. [lxv] By the 1840s Boston, Philadelphia, and several smaller fairs were receiving material and moral support from anti-slavery advocates in Ireland, Scotland, and Britain. [lxvi] Selling foreign goods helped to boost attendance from the general public to the fairs. Sales of British goods alone brought in almost half of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society’s treasury income in the 1850s. [lxvii]

Philadelphia’s Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS), founded by Lucretia Mott and others in 1833, also held anti-slavery fairs for at least twenty years from 1836-1855. [lxviii] Notably, the Eleventh Anti-Slavery Fair in December, 1846 was written about at length by Horace Greeley, Samuel B. Parsons’ friend who was editor of the New York Tribune. [lxix] The twentieth anniversary Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery fair was advertised in 1855 with an announcement signed by several women, including Lucretia Mott, Jane Bowne Haine’s fellow Nine Partners alumna, asking for contributions in money or goods. [lxx]

Some anti-slavery fairs were also held in New York; not as many posters are extant as for Boston and Philadelphia, even though one source has claimed they began spreading across New York State near the end of the 1830s. [lxxi] More are known in upstate New York than in New York City. For example, one poster from 1839 in Syracuse advertised a fair organized there by the Ladies Anti-Slavery Committee. [lxxii] Another from 1849 in Victor, New York advertised an anti-slavery fair organized by the ladies and friends of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society. Another newspaper article referred to a two-day fair in 1846 given by Ladies of the Anti-Slavery Society in Buffalo, with receipts of $50 a day. [lxxiii] Fairs were also held in Junius, Seneca Falls, Victoria and Waterloo, besides Rochester, New York. [lxxiv]

Less evidence remains so far of Anti-Slavery fairs in the New York City area in the 1830s and 1840s. It leads one to wonder whether there was a conservative backlash in New York City to openly advertising such public anti-slavery activities at the time. [lxxv] Many factors may have contributed to this: New York’s abolition of slavery at a later date than Massachusetts and Pennsylvania; New York City’s economic ties to slavery even after it had been abolished; the reluctance of some conservative papers to publish content viewed as controversial and political; and what may have been a deliberate choice by activists to place notices only in anti-slavery newspapers.

Notably, a Ladies’ New York City Anti-Slavery Society was controversial and short-lived, only lasting from approximately 1835 until 1840; its demise stemmed partially from its refusal to racially integrate. [lxxvi] Nevertheless, Julianna Tappan, daughter of famed New York abolitionist Lewis Tappan, is believed to have worked with the group to organize fairs. [lxxvii] Underground Railroad agent Abigail Hopper Gibbons has also been mentioned as an avid fair supporter. [lxxviii] The African American women at the Broadway Tabernacle are also mentioned as holding an annual fair to raise money for the New York Vigilance Committee. [lxxix]

In 1851, an Anti-Slavery fair held on Thanksgiving in Montague Hall in Brooklyn was noted to have raised $950. Over 1,000 visitors were admitted. [lxxx] Since considerable goods remained, they were to be given to a fair to be held in New York. Speakers at the fair included the well-known Congregational anti-slavery preacher Henry Ward Beecher from Plymouth Church in Brooklyn; the Hon. E.D. Culver, a Brooklyn attorney, judge, and politician; Rev. Evan Johnson, an Episcopal minister who established St. Michael’s church in Brooklyn; and Rev. Pennington, a former escaped slave who notably was friends with Simeon Jocelyn and Lewis Tappan, anti-slavery activists who have both been linked with the Parsons brothers through correspondence in the Bowne House Archives and other repositories. Significantly, Pennington also believed in the power of education as intertwined with the anti- slavery movement, just as the Quakers did.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 5, 1851

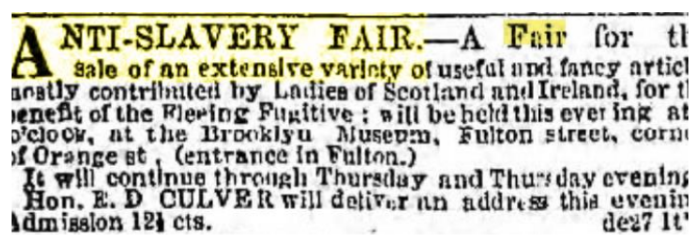

At another Brooklyn anti-slavery fair held at the Brooklyn Museum in December, 1854, the Hon. E.D. Culver was identified as the sole speaker.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 27, 1854

One Manhattan fair at Clinton Hall at Astor Place was advertised in December, 1856, with provisions or money to be sent to the Anti-Slavery office on Nassau Street or Clinton Hall:

New York Tribune, December 18, 1856

Another held at Clinton Hall in December, 1857, openly advertised that the object of the fair “is partly to aid fugitive slaves passing through New York…”.

New York Times, December 10, 1857

Although we have not yet found any advertisements for Anti-Slavery fairs in Queens, we have established in previous articles that Robert Bowne Parsons, one of Mary Bowne Parsons’ sons, helped to establish an anti-slavery First Congregationalist church in 1851 on Bowne Street, just one block away from the Bowne House. One cannot help but wonder if Anti-Slavery fairs could have been held there, whether openly advertised or not, or whether evidence of any advertisements exist to this day. We also know that the Parsons had contacts with Henry Ward Beecher, Lewis Tappan, and other anti-slavery activists in Brooklyn, and with the New York Vigilance Committee in Manhattan. They also had family connections in the Philadelphia area such as Jane Bowne Haines and other Nine Partners alumna, and in Massachusetts through Samuel B. Parsons’ wife, Susan (Howland) Parsons, and her family.

Quaker women courageously used both hidden voices and outspoken voices by participating in anti-slavery sewing circles and otherwise contributing their needlecraft in support of each wave of the 19th century Abolitionist and Free School movements. These contributions have long been underestimated, not only in the critical fundraising they provided to support anti-slavery societies throughout the Northeast, but in how they undertook to fill a void in providing free education to African-American children decades before the public schools finally made such a commitment. Bowne and Parsons women were among these unsung heroes and are to be commended for all their contributions. The time is long overdue to also investigate and recognize the contribution which black female artisans, including those in the greater Flushing free black community, made with their own needlecraft to these causes.

ENDNOTES & REFERENCES

[i] Credit Line: Purchase, Anna Glen B. Vietor Gift, in memory of her husband, Alexander Orr Vietor, 2009.

[ii] Jones, Rufus, Matthew, et al., “May 28, 1768, The New York Yearly Meeting,” in The Quakers in the American Colonies, (London: Macmillan and Co., 1911), 257.

[iii] Jones, 258.

[iv] “Quakers and Slavery Resources: Timeline,” from Quakers and Slavery, online exhibit from Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections, 2011, https://web.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/speccoll/quakersandslavery/resources/timeline.php.

[v] Hum, Tarry, “Black Dispossession and the Making of Downtown Flushing,” Progressive City, https://www.progressivecity.net/single-post/black-dispossession-and-the-making-of-downtown-flushing (Accessed September 24, 2022); Antos, Jason D., “A.M.E. has Served Flushing for 200 Years, Gazette, March 2, 2011, https://www.qgazette.com/articles/ame-church-has-served-flushing-for-200-years/.

[vi] Historical Perspectives, Inc., Flushing Center CEQR 86-337 Q, Phase IA Archaeological Assessment Report for the Flushing Center Project (June 7, 1988), http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/526.pdf, 25; “Macedonia A.M.E. Church,” NYC Ago, http://www.nycago.org/Organs/Qns/html/MacedoniaAME.html (Accessed September 24, 2022).

[vii] Sandy Ground Historical Society, Inc., https://sandyground.wordpress.com/ (Accessed September 10, 2022); see also “The Sandy Ground Community, (New York) is Founded,” African American Registry, https://aaregistry.org/story/sandy-ground-community-founded/ (Accessed September 10, 2022).

[viii] Weeksville Heritage Center, https://www.weeksvillesociety.org/ (Accessed September 10, 2022).

[ix] “Central Park and the Destruction of Seneca Village,” Urban Archive, June, 2, 2020, https://www.urbanarchive.org/stories/c4UxttDrUH4?gclid=Cj0KCQjwj7CZBhDHARIsAPPWv3fu803uvA_zDt2iyCPhO axr7PEtCfRUJDxwxL2kixo5_TE_xlH2wB8aAqgGEALw_wcB.

[x] An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, March 29, 1799, New York State Archives Digital Collections, NYSA_13036-78_L1799_Ch062, https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/10815.

[xi] An Act Relative to Slaves and Servants, March 31, 1817, New York State Archives, Digital Collections, NYSA_13036-78_L1817_Ch137_p2, https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/10817.

[xii] Van Broekhaven, Deborah, “’Better than a Clay Club’” The Organization of Anti-Slavery Fairs, 1835-1860,” Slavery and Abolition, Vol. 19, No.1, 24-45, April 1998, DOI: 10.1080/01440399808575227; https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01440399808575227.

[xiii] Kashatus, William C. III, “The Inner Light and Popular Enlightenment: Philadelphia Quakers and Charity Schooling, 1790-1820,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography, Vol. CXVIII, Nos. ½ (Ja. /April 1994). https://www.jstor.org/stable/20092846. Reference provided by Kate Lynch.

[xiv] McCarthy, Andy, “Class Act: Researching New York City Schools with Local History Collections,” October 20, 2014, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2014/10/20/researching-nyc-schools.

[xv] Andrews, Charles C., The History of the New York African Free Schools: From Their Establishment in 1787 to the Present Time: Embracing a Period of More Than Forty Years (1830); republished by (Creative Media Partners, LLC , 2018); see also Hofer, Margi, video presentation on “‘Truth Revealed’: Rosena Disery’s African Free School Sampler” (Curator Confidential), New York Historical Society, February 10, 2021, https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=0hzRBeYNGV8&t=159s&pp=2AGfAZACAQ%3D%3D.

[xvi] McCarthy, “Class Act”; see also Gill, John Freeman, “Trying to Save The City’s Last ‘Colored School’,” NY Times, Real Estate, October 9, 2022, 1, 8, stating that afterward, the schools were transferred to the Board of Education in 1853. In 1873, New York State passed a law prohibiting school officials from denying children access to any public school “on account of color” and the Board of Education’s by-laws were amended in 1884 to abolish the “colored “schools, with two exceptions.

[xvii] Hofer, “Truth Revealed,” at 12:19.

[xviii] We know that Rosena Diary later married a prominent African-American businessman Peter Van Dyke who ran a well-known catering business; her occupation was listed as “Caterer” and “Cook. Hofer, “Truth Revealed,” at 19:34.

[xix] Hofer, “Truth Revealed,” at 3:10.

[xx] Hofer, “Truth Revealed,” at 7:27. See generally, “New-York African Free School Examination Days,”and AFS records, 1817-1832, “Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May Be Liberated,” https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A139382.

[xxi] A document found by Kate Lynch in “The Edmund A. Stanley Jr. collection relating to Bowne & Co.” in the New York Public Library, Manuscripts & Archives (Schwarzman Building) relating to the Association of Women Friends for the Relief of the Poor, dated June 8, 1801, states that the organization, “having concluded that a part of their funds should be appropriated to the education of poor children ...whose parents belong to no religious society and who ...cannot be admitted to any of the charity schools of the city,” have appointed a committee to open a school. Among the committee members were Caroline Bowne and Hannah Bowne, one of Robert Bowne’s daughters. See also McCarthy, “Class Act,” stating the first FA school was in 1802; Ring, Betty, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (Two Volumes) (New York: Knopf, 1993), 318. Betty Ring contends that the predecessor Quaker female organization to the Manhattan FA was formed in 1798 and that the first co- educational school opened in 1801, citing Bourne, History of the Public School Society of the City of New York (1873). She also writes that the FA was merged into the PSS in 1845 while McCarthy states it was merged with the Board of Education at that time.

[xxii] McCarthy, “Class Act.”

[xxiii] McCarthy, “Class Act.”

[xxiv] Three years later, the Free School Society, later known as the Public School Society (PSS), was organized, operating the first free schools in the state for boys in 1809. John Murray, Jr., husband of Catharine (Bowne) Murray, helped to form the initial Free School Society, along with other members of the New York Manumission Society. In 1842, the New York State Legislature finally created a Board of Education charged with operating public schools, with control given to local boards. The Manhattan FA girls’ schools were absorbed in 1845, while the PSS (including the former AFS) merged with the Board in 1853. McCarthy, “Class Act.”

[xxv] Ring, Betty, Girlhood Embroidery, 318; “Samplings,” M. Finkel & Daughter, http://samplings.com/catalogue/xxiii, 2 (Accessed September 12, 2022).

[xxvi] Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 318; “Samplings,” M. Finkel & Daughter, http://samplings.com/catalogue/xxiii , 2 (Accessed September 12, 2022); cf. 1814 sampler of Mary Martin, Female Association school for Colonel Henry Rutgers, who may have been a benefactor of the Free School Society, New York Historical Society collection, https://emuseum.nyhistory.org/objects/7388/sampler.

[xxvii] “Samplings,” M. Finkel & Daughter, Anna Bowne sampler, http://samplings.com/sampler/anna-bowne ; Hofer (Accessed September 12, 2022), “Truth Revealed,” at 14:25.

[xviii] A sampler made by a Mary Wetmore for Sarah Herbert entitled “Industry” from School No. 2 has been researched and catalogued at Finkel & Daughter, http://samplings.com/catalogue/xlv, 5 (Accessed September 12, 2022). They note that Betty Ring also previously had in her collection a sampler made by Ann Heyden for a Maria Franklin at School No. 2 in 1815.

[xxix] Hofer, “Truth Revealed.” at 13:54. Historians have debated whether Lucy Turpen was white or African-American, but Kate Lynch has determined that she was white from examining Ohio census records after her later move there.

[xxx] According to staff at the Wyck House, there are also anti-slavery pamphlets in the collection which Jane and her husband Reuben gave to their children; and among her possessions at the Wyck House is an English serving dish by John Ridgway and Co. with a kneeling slave and the text “Am I not a man and a brother?” made to support the anti-slavery movement. Kate Lynch is credited with bringing the Lucy Turpen sampler for Jane Bowne Haines to the Bowne House’s attention in connection with her research.

[xxxi] Johnson House Historic Site, https://www.johnsonhouse.org/; (Accessed September 20, 2022).

[xxxii] “Independent Minds: Bowne & Parsons Women,” 2018 Newsletter of Bowne House Historical Society, Inc.; Murray, Charlotte, Flushing Female Association, 1814-1967, compiled in part by Miss Jennie C. Bloodgood, 1914.

[xxxiii] “FFA Account ledger” from 1814-, Queens Historical Society collection.

[xxxiv] “FFA Account Ledger,” Queens Historical Society collection.

[xxxv] Murray, 5.

[xxxvi] For example, the Bowne House collection includes a sampler made by Mary Parson’s eight-year-old daughter Mary B. Parsons in 1821 and the 1821 sampler made by one member Abigail Smith for Mary Parsons, another member, is shown in the text above. See also Angelina. “Bowne Women and Their Roles in Popularizing Education, 2013 Newsletter of the Bowne House Historical Society, Inc.,” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e29d4d91e118a3f8cb62233/t/6318d6b6c7a36c0befba3f81/16625722178/bownenewsletter_oct2013.pdf.

[xxxvii] See 1816 student sampler by Jane Post, for Maria Farrington, a member of the Flushing Female Association displayed in Murray, Charlotte, Flushing Female Association, 8; Flushing CEQR, 28.

[xxxviii] “Samplings” M. Finkel & Daughter, http://samplings.com/catalogue/xxiii, 2.

[xxxix] http://samplings.com/catalogue/xxiii , 2.

[xl] Flushing Center CEQR, 28. See also “Independent Minds: Bowne & Parsons Women,”.

[xli] In 1843, the Board of Education requested that the FFA disperse and give their property to it for a new school but the FFA refused on the basis that funds had been given to them for their charitable educational purpose. Apparently, another “colored school” was also operating by that time in Flushing. Letter from Charles U. Powell to Henry J. Cadbury., January 13, 1939, Henry J. Cadbury Papers in Haverford Quaker and Special Collections, https://m.box.com/shared_item/https%3A%2F%2Fhaverford.box.com%2Fs%2Fzvbnijek8op6rt16w2q5pxwhgf0hym4u. Reference provided by Kate Lynch.

[xlii] “FFA Account ledger,” Queens Historical Society collection. In Matthew Franklin’s will, he directed his executors to spend 150 pounds for books and education of poor black children, “them that their parents did belong among the people called Quakers.”

[xliii] Murray, 7 and 8. Murray includes an image of an 1816 sampler worked by Jane Post at an FFA School for Maria Farrington, an original member of the FFA; see also Flushing Center CEQR, 28.

[xliv] Flushing Center CEQR, 28.

[xlv] “The Underground Railroad in the New York Hudson Valley,” fb, fergus m. bordewich: the imperfect union, July 28, 2005, http://www.fergusbordewich.com/blog/?p=38 ; “Nine Partners Monthly Meeting Manumissions,” https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/manumissions/Nine%20Partners%20Monthly%20Meeting%20Manumissions.csv. See also

https://archives.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/repositories/9/resources/5270/collection_organization.

[xlvi] Bordewich, “The Underground Railroad in the New York Hudson Valley.” See also Nine Partners 1815 document, with responses teachers may give to students about slavery, Oakwood Friends School Archives.

[xlvii] Talcott, Joseph, The Memoirs of Joseph Talcott (Auburn, N.Y.: Miller, Orton, and Mulligan, 1855), 13-16, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/LaxWacPNE5MC?hl=en&gbpv=1. Talcott’s role as founder has also been confirmed by the Oakwood (former Nine Partners) archivist. See also Dulworth, Sherrie, “Were the Underhills of Yorktown Unrecognized Abolitionists?” Examiner News, July 13, 2022, https://www.theexaminernews.com/were-the-underhills-of-yorktown-unrecognized-abolitionists/.

[xlviii] Talcott, The Memoirs, 271-73.

[xlix] Talcott,The Memoirs, 13-15. See Ring, Betty, Volume II of Girlhood Embroidery for discussion of Nine Partners and samplers, 306.

[l] Talcott, The Memoirs, 24. Talcott mentions that thereafter from time to time the New York Meeting appointed committees to carefully supervise Nine Partners, suggesting that the Meeting fully encouraged its anti-slavery message and educational training.

[li] Dulworth, Sherri, “Hudson Valley Abolitionists, Along the Freedom Movement from Queens to Albany,” https://www.theexaminernews.com/hudson-valley-abolitionists/, Examiner News, February 18, 2022.

[lii] Katz, William Loren, “The Women Who Gave Us Christmas,” The Howard Zinn Project, 2010, https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/women-who-gave-us-christmas. See also Van Broekhaven, 25, citing William Lloyd Garrison- “One living Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle is worth more to humanity than all the Clay Clubs, and Taylor clubs, and Democratic Clubs that ever have been or ever will be,” 36-37; also stating the Philadelphia fair committee published fair reports and sent formal thanks to the “20 circles of women from outside the city who sewed for the Philadelphia Fair”; See also Female Anti-Slavery Sewing Society records, https://archives.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/resources/hcmc-975-09-010.

[liii] Van Broekhaven, 25.

[liv] Van Broekhaven, 25.

[lv] Van Broekhaven, 32.

[lvi] “Crafting Black Dolls: The Women Behind the Needle, “Center for Women’s History, New York Historical Society, April 03, 2022, https://youtu.be/SkaR6-RCd_k.

[lvii] “Crafting Black Dolls,” See also Van Broekhaven, describing watch fobs made by girls with this motto, 32.

[lviii] Sharon Collects: The Sampler Collection of Alexandra Peters, June 18, 2022 opening, https://sharonhist.org/event/on-view-alexandra-peters-sampler-collection/.

[lix] Van Broekhaven, 30.

[lx] Van Broekhaven, 41, fn. 5, citing Hewitt, Nancy, “The Social Origins of Women’s Antislavery Politics in Western New York”, and her book, Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822-1872 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1984).

[lxi] 1844 Anti-Slavery Broadside, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.05801300/.

[lxii] Jake S, “The Anti-Slavery Fair,” The Boston Public Library, August 8, 2018, https://www.bpl.org/blogs/post/the-anti-slavery-fair/.

[lxiii] Jake S.; see also Anti-Slavery poster at Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.24800700/.

[lxiv] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 24, 1844; Evening Post, January 26, 1844.

[lxv] Van Broekhaven, 31.

[lxvi] Van Broekhaven, 31.

[lxvii] Van Broekhaven, 31.

[lxviii] Van Broekhaven, 25; “Lucretia Mott, (1793-1880),” National Women’s History Museum, ed. Michal, Deborah, PhD. (2017), https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lucretia-mott.; Soderland, Jean R., “Priorities and Power: The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society” in Yellin, Jean Fagan, and Van Horne, John C.(eds.), Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America (Ithaca, 1994), 80-86.

[lxix] New York Tribune, December 25, 1846.

[lxx] New York Daily Herald, November 24, 1855.

[lxxi] Snodgrass, Mary Ellen, The Underground Railroad, An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations, (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc, 2008), 30-31.

[lxxii] Ladies Anti-Slavery Fair (Syracuse, N. Y.), New York Public Library, https://browse.nypl.org/iii/encore/search/C__SLadies%27%20Anti%20Slavery%20Committee%20%28Syracuse%2C%20N.Y.%29__Orightresult?lang=eng&suite=def.

[lxxiii] New York Tribune, January 9, 1846.

[lxxiv] See, e.g., Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad, 30; Mandell, Hinda, “Rochester’s Ladies Anti-Slavery (Sewing) Society: Handcraft as a Metaphorical Tool for the Abolitionist Cause,” Journal of Feminist Scholarship, Vol. 20, 49-66. ( Spring 2022); https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol20//.

[lxxv] For example, one brief and vague note in the New York Daily Herald on December 11, 1857 stated “We see that an anti-slavery fair has just been held somewhere in town. It was for the benefit of the underground railroad, but it turned out to be a very small concern.” The writer suggested that if Senator Douglas and Governor Walker had been invited it would have made some excitement and increased the receipts, “which it appears were very poor.”

[lxxvi] Swerdlow, Amy, “Abolition’s Conservative Sisters: The Ladies New York City Anti-Slavery Societies, 1834-1840”, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7591/9781501711428-006/pdf.

[lxxvii] Van Broekhaven, fn. 40. See also 1837 letter from Juliana Tappan to Anne Warren Weston regarding anti-slavery goods; https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/book_viewer/commonwealth:2z1106595.

[lxxviii] Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad, 30, 217, citing Bacon, Margaret Hope, Abby Hopper Gibbons, Prison Reformer and Social Activist (Albany: SUNY Press, 2000).

[lxxix] Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad, 30.

[lxxx] New York Daily Tribune, November 29, 1851.