Due to his name, Lawrence Dutch has traditionally been regarded as the only Dutch founder of the English town of Flushing. However, in his “Profiles of Selected Kieft Patentees of Flushing, 1645,” B. Purcell Robinson states that “Dutch” is a transcription error of the kind later associated with Ellis Island, and identifies him with a Dane named Laurens Duyts, familiarly known as “Laurens Grootshoe” (essentially “Bigfoot.”) No surviving records connect Duyts directly to Flushing; however, the registry of New Netherland yields no better matches, and Duyts did engage in farming in Newtown, where other Flushing patentees soon moved.

Laurens Duyts was born around 1612 on the North Sea island of Nordstrand in Holstein, now the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein. In 1634, most of the island was destroyed in a storm surge. Denmark was not a colonial power, so its economic refugees had to join the settlement efforts of other powers. By 1638 Duyts had migrated to Amsterdam, where he married a Dutch woman of 18, Itye Jansen of Oldenburgh. The church register describes him as a laborer residing at the Brouwersgracht, a canal lined with breweries. In 1639 the Duytses sailed for New Netherland aboard De Brant van Trogen, or The Fire of Troy, under fellow Dane Capt. Peter Kuyter, who would settle East Harlem, and his partner Jonas Bronck, for whom the Bronx is named. Duyts and his friend Pieter Andriesen came as indentured servants to Bronck. Following their arrival in New Ansterdam, a contract dated July 21, 1639 commited them to cultivate a tract of wilderness “on the mainland opposite to the flats of Manhates,” with permission to grow their own maize and tobacco, on condition that every two years they break new land and surrender the previous plot for Bronck’s use. From the proceeds the two would repay their passage money, “in tobacco or otherwise.” The illiterate Duyts signed with a mark.

“The invisible hand of the Almighty Father surely guided me to this beautiful country, a land covered with virgin forest and unlimited opportunities. It is a veritable paradise and needs but the industrious hand of man to make it the finest and most beautiful region in all the world.” - Jonas Bronck

Detail from 1639 map “Manhattan Lying on the North River.” North River = Hudson River; Bronck’s homestead is number 43 in the key. (Library of Congress.)

Duyts and Andriesen accompanied Bronck across the Harlem River to a tract of over 500 acres purchased from the Wecquaesgeek Indians. The 1639 map above shows Bronck’s homestead at the southern tip of the mainland in present-day Mott Haven, across from Randall’s Island. Bronck named his land “Emmaus,” after the Biblical town where Christ appeared after the Resurrection. (Thanks to the “industrious hand of man,” the site is currently occupied by Harlem River Yards and its solid waste processing plant.)

“Signing the Peace Treaty with the Indians.”

Bronck’s imported labor force soon erected a stone house with tile roof “in the style of a Dutch fort,” a barn, tobacco houses, and barracks. The Duyts family grew with the farm; daughter Margariet was baptised on December 23, 1639 in the Dutch Reformed Church at Manhattan, and son Jan followed on March 23, 1641, with Captain Kuyter as godfather. In April 1642 Duyts may have witnessed history on this far-flung “outplantation,” when the Dutch signed a peace treaty with Wecquaesgeek sachems Ranaqua and Tackamuck at Bronck’s farmhouse following an abortive raid on the Indian village at Yonkers. Sadly, Bronx’s peacemaking unraveled after Kieft’s War broke out in 1643, and Bronck himself died before May 6th of that year. With Indian-settler relations tense and the farm changing hands, Duyts needed a fresh start.

Why would this Dane head to English Flushing, and not his countryman Captain Kuyter’s settlement just across the river in Harlem? The answer may lie in the New York State Archives. On June 25, 1643, Englishman Thomas Spicer, formerly of Rhode Island, signed a lease for the former Bronck farm. Several of Spicer’s old neighbors, including Charter signer Thomas Beddard and Remonstrance signer George Clere, would shortly become Flushing residents, and perhaps he suggested to the displaced sharecropper that he follow their lead. Following the baptism of their son Hans in 1644, the family disappears from the Dutch records for several years. If Duyts did start a new life as “Lawrence Dutch,” he left no lasting trace in Flushing, and starting in 1653 he resurfaces regularly in the court records of New Amsterdam, alongside parties bearing almost exclusively Dutch or Scandinavian names.

Duyts appeared some dozen times before the Court of Burghomasters and Schepens and the New Netherland Council. Not all of this activity was litigious; in 1640 he witnessed a promissory note for his brother-in-law, Garret Jansen, and in 1643 a cobbler’s deposition records that another man robbed Duyts of some leather. In 1653 he was sued by his former partner Pieter Andriesen, who had become a man of means even as Duyts remained a farmer- acquiring a tavern license, a chimneysweeping business, and even African slaves. The court minutes give no details of the dispute, as Duyts sent a representative without a proper power of attorney, and was deemed in default.

In 1654 Captain Francis Fyn accused Duyts of attempting to sell land “over against Hog Island” that Fyn held title to. “Hog Island” is now Roosevelt Island, placing the contested property near the Long Island City waterfront. Fyn’s patent was sealed but not signed, so the court referred the case to Director Stuyvesant. In 1657 Fyn again sued Duyts and a co-defendant for selling crops before paying their rent, in violation of their lease. A final determination on these cases was never entered, but they establish Duyts’ continued activity in Newtown, Flushing’s neighbor to the west.

There were further suits, the details of which are often sketchy or confused, but which nonetheless paint a vivid portrait of the hardscrabble life of the colony, with its barter economy and oral contracts between illiterate people. There are suits over non-payment for 20 wagonloads of hay delivered to Claes van Ruyter “in the Valley”; over who owed the carter for lost wages; over crops purportedly embezzled by “Jan the Soldier” Hendricks, who was demanding 200 florins for tobacco he’d allegedly seized; over Duyts’ landlord’s outstanding debt for some meat, for which Duyts was served with a arrest warrant. In May 1658 grande dame Annetke Bogardus, widow of the Dutch Reform Minister, demanded two hogs from “Lauwerence Grootshoe” in lieu of unpaid rent for the Bouwerie (farm) that Duyts sublet from the delinquent meat buyer in the previous case. Overall, Duyts appears three times as a victim or plaintiff, three times as a witness, and seven times as a defendant or co-defendant. The cases deal with minor debts, property disputes, and business deals gone sour; at worst the profile of a petty grifter. Events then take a dramatic turn.

Our authority B. Purcell Robinson notes that after 1658 Duyts mysteriously disappears from the record for ten years. However, Mr. Robinson toiled in the days before the Internet, when the Minutes of the Council of New Netherland were not yet digitized. The following documents finally explain the lost decade.

On November 18, 1658, an order was issued to interrogate Geesje Jansen, a woman accused of having illicit intercourse with Duyts. Geesje may have been the sister of Duyts’ wife Isje Jansen.

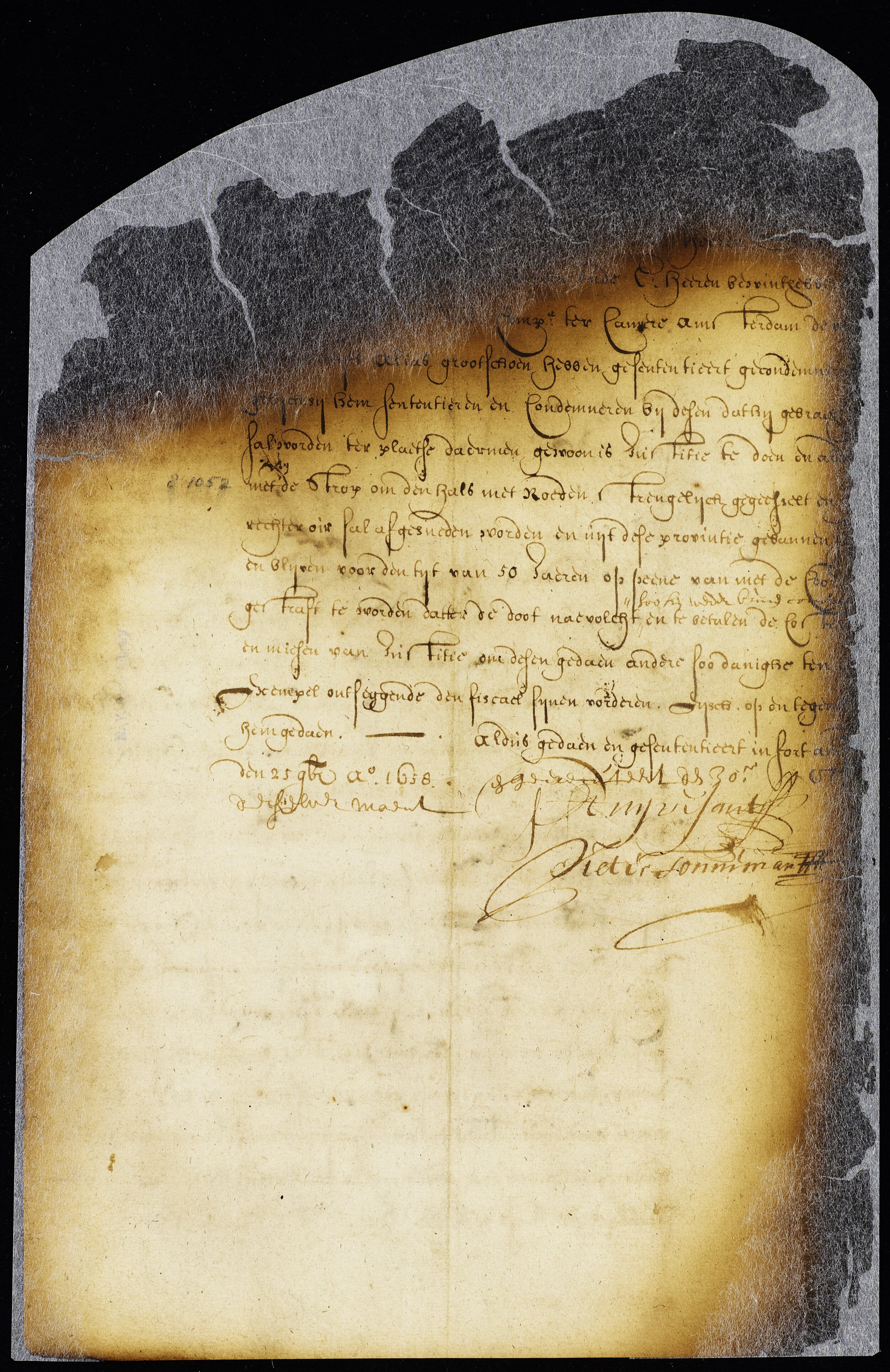

On November 25, 1658 the following eye-popping decree was recorded: “Sentence. Laurens Duyts, of Holstein, for selling his wife, Ytie Jansen, and forcing her to live in adultery with another man, and for living himself also in adultery, to have a rope tied around his neck, and then to be severely flogged, to have his right ear cut off, and to be banished for 50 years.”

Geesje Jansen was displayed half-naked on the pillory with two iron bars in her hands, and banished for 30 years. The other man -identified as John Purcell, alias Botcher, of Huntingdonshire, England- was also pilloried, fined 100 guilders plus court costs, and banished for 20 years. Itye Jansen, seemingly the victim, was punished as an adulteress herself, with whipping and banishment for an unknown period. It seems that the two unmarried adulterers were spared corporal punishment.

This foray into sexual trafficking, spousal abuse, and adultery would indeed seem to auger the end of Duyts’s career in New Netherland, and within a week, at least two people requested liens on Duyt’s property. Duyts moved to Bergen, New Jersey, where eight years later he married Geesje Jansen. Their daughter Catherine was baptized in 1667.

On 12 January 1667-8 Duyts makes his final appearance in the Court records of New Amsterdam, now ruled by the English. A baker and a laborer were disputing the rights to a canoeload of grain sold by Laurens Duyts, now deceased. Duyts had ordered it delivered to the baker, but he died owing back wages to the employee who had helped row the grain across the East River. Noting the geography, it seems that after the English takeover in 1664, Duyts may have felt at liberty to resume farming on Long Island, even with John Parcell alias “Botcher” and his ex-wife Itye still resident in Newtown.

The aftermath suggests that the whole sordid affair may have been less sordid, and more consensual, than Duyts’ sentence suggests. In December 1658 Ytie Jansen and John Parcell petitioned the court as “two sorrowful sinners” for a pardon and leave to marry. They were ordered to separate and given three months to leave the province. However, it seems that instead they quietly remained in Newtown and had two children together. The Duytses’ adult sons did business with Parcell, evidently not shunning him as their mother’s kidnapper. A court record from 1684 describes Ytie as Purcell’s widow, so they must have eventually married. Was Duyts truly the “black sheep” of the Flushing Charter signers, a monster who sold his wife into sexual slavery, which she then reconciled herself to? Or were all four people simply taking advantage of the relative freedom of frontier life to seek happiness in an unconventional living arrangement? From the distance of 2020, it is hard to judge.

Our research is a work in progress. Bowne House welcomes new information on the Charter Signers and early Flushing history. If you believe you are descended from Lawrence Dutch/Laurens Duyts, or have information about him, please contact us at office@bownehouse.org