Thomas Farrington’s untimely death ended his history in Flushing shortly after he signed the Charter. We do not know his date or cause of death, only that in August 1646 his widow remarried. His only child, Thomas Farrington, Jr., moved upstate. The Farrington family thus owes its legacy in Flushing to Thomas’s brother Edward, who followed him to the town. It was Edward who induced the Bownes to settle there following his marriage to Dorothy Bowne, who signed the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance, and who founded one of the area’s leading Quaker families. Thomas himself might be considered more a “Founding Uncle” of the town than a Founding Father. However, in his brief life he co-founded not just one but two Colonial towns, including the first English settlement on Long Island.

Beginnings in Buckinghamshire

Old Olney Bridge, Buckinghamshire, by William Samuel Wright, 1815–1915. (The Cowper and Newton Museum)

Thomas Farrington’s origins at least are documented, unlike those of a number of his fellow Charter signers we have examined. He was born to Edmund Farrington and Elizabeth Newhall around 1614 in the English county of Buckinghamshire, probably in the village of Sherington where his parents wed. The family soon moved to nearby Olney, a market town remembered today as the site of a battle in the English Civil War. In later life Edmund Farrington took on an apprentice “fulmonger,” or dealer in hides; he also operated a grist mill. However, it’s unclear whether he brought up his sons to either occupation. In April 1635 Thomas’s parents and four youngest siblings- Sarah, Mathew, John, and Elizabeth- joined the Puritan Great Migration and emigrated to the Bay Colony aboard the Hopewell. The passenger list records that Edmund Farrington took the “Oath of Allegiance and Supremacy,” in which would-be emigrés affirmed the King as head of the Church of England, and thus their religious orthodoxy. By 1638 Edmund owned 200 acres in Lynn, Massachussetts. Thomas and his brother Edward, the eldest children, must have emigrated separately.

Striking Out on Long Island: The Settlement of Southampton

In March 1639/40 Thomas Farrington, his father Edmund, and his brother John appear on a list of twenty “undertakers” of the first English plantation on Long Island. Edmund was one of eight investors who financed a vessel and hired a captain to transport the settlers and their cargo. He signed the “Disposall of the Vessel” with his mark; however, both his sons were literate and signed their names. Apparently, this was an upwardly mobile family. Unlike the founders of Rhode Island, the Long Island pioneers were not driven out of Massachusetts by religious persecution; Governor Winthrop wrote that the Lynn residents simply “found themselves straitened for land.” The “undertakers” even promised that once they were sent a minister from Massachusetts, they would voluntarily surrender all administrative authority in the new plantation to the Church. They left armed with a patent for eight square miles anywhere on Long Island signed by James Farrett, agent for the Scottish Earl of Stirling, who had just been granted Long Island by King Charles I of England. The Crown was eager to block Dutch expansion, and Charles’ gift to his favored courtier simply disregarded the existing Dutch settlement on the Island.

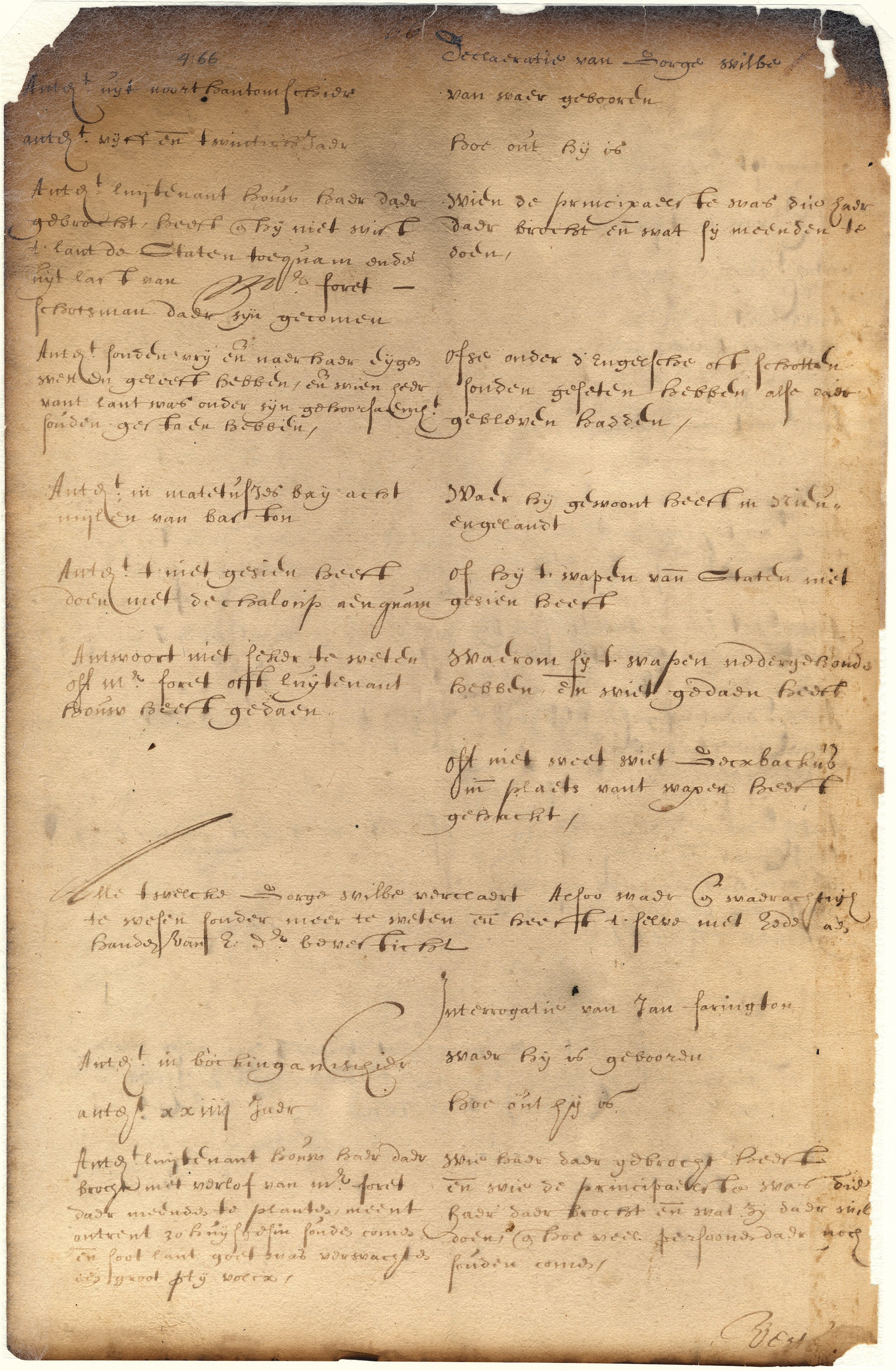

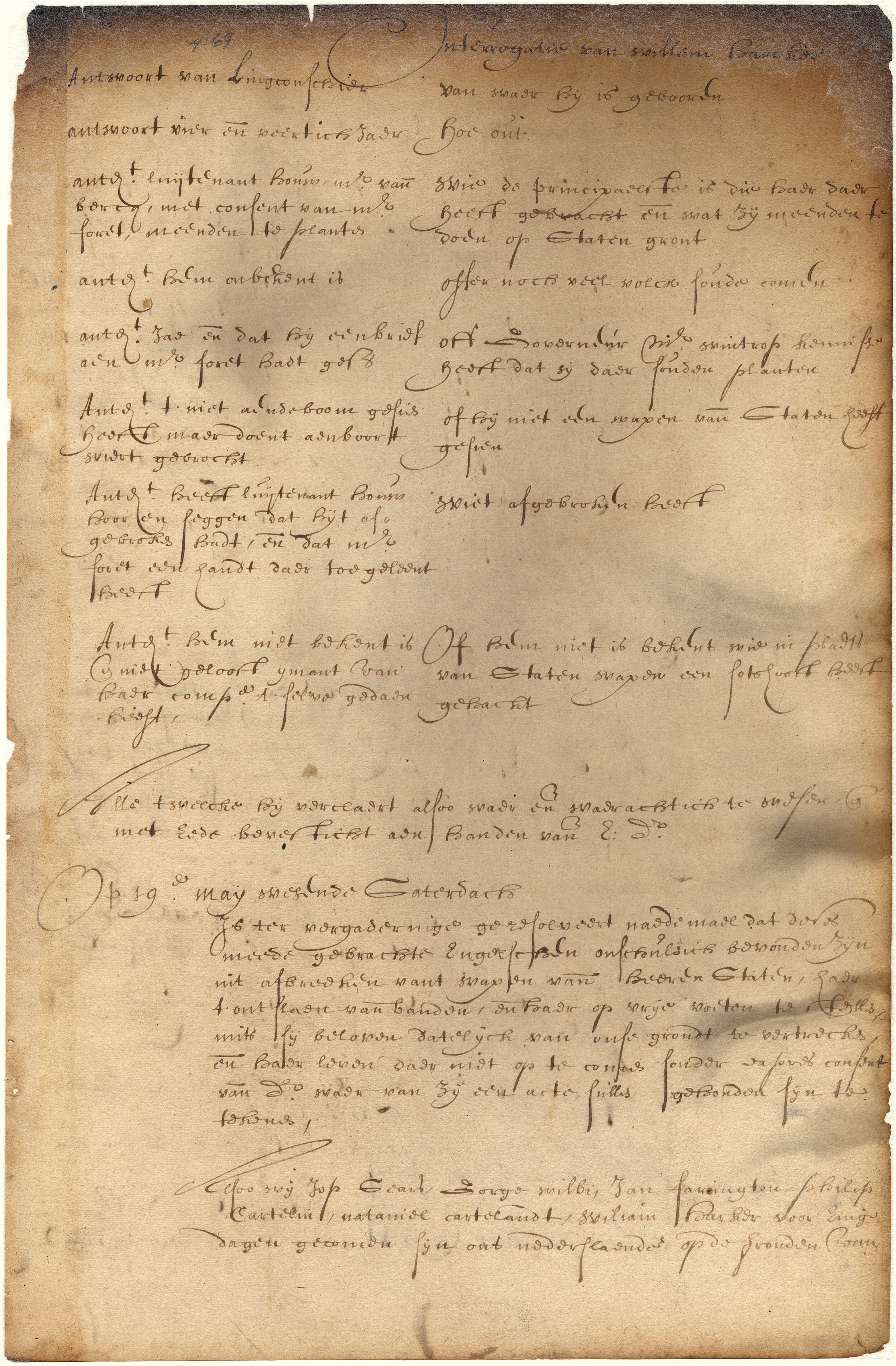

In May 1940 an advance party of 10, including John Farrington, disembarked in Schout’s Bay near present-day Manhasset, where they found the coat of arms of the Dutch States-General (the governing body of the Netherlands) nailed to a tree. Undeterred, they began clearing the wilderness. Their arrival nearly caused an international incident, as appears in the New Netherland Council minutes of May 13, 1640. The Dutch had just purchased the land in question from Sachem Penhawitz of the Canarsie Indians, who promptly reported the “interlopers and vagabonds” to the Council of New Netherland. A Dutch scout sent to reconnoiter observed the English already building houses, also noting that the Dutch Arms had been torn down. Worse yet, “a Fool’s face” had been carved in their place, “this being a crime of Lèse-Majesté [insult to the State] and tending to the disparagement of the sovereignty of their High Mightinesses.” On May 14, Secretary Tienhoven arrived before dawn with an entourage of 25 soldiers and arrested six Englishmen. They left behind a woman and small child with two unnamed men, possibly including Thomas Farrington- indeed, the small party contained one other pair of brothers. The interrogation of “Jan Farington” is preserved in the New York State Archives. He and the others wisely blamed James Farrett, safely at his home in New Haven, and Lieutenant Howe, the skipper of the departed boat, for vandalizing the Arms, while professing total ignorance of the “Fool’s face.” On May 19 the prisoners were released, on condition that they leave Dutch territory immediately “on pain of being punished as perverse usurpers.”

Conscience Point National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) “Near this spot in 1640 landed the colonists from Lynn, Mass. who founded Southampton - the first English settlement on Long Island.”

On June 10th, 1640, Farrett issued the undertakers another patent, for "all those lands…between Peaconeck [Peconic] and the easternmost point of Long Island with the whole breadth of the said Island from sea to sea..." -as far from the Dutch as they could get. The settlers were obligated to buy the land from the local Indians, and to pay the Earl of Stirling four bushels of prime Indian corn each year. Later that month they disembarked at “Conscience Point” off Peconic Bay, today a wildlife refuge where a stone marker stands in their honor. Striking an informal agreement with the Shinnecock near the Indian village of Agawam on the south shore, they founded Southampton in the area today known as Old Town, east of present-day Main Street. On December 13, 1640, the Native owners Pomatuck, Mandush, Macomanto, Pathemanto, Wybbenett, Wainmenowog, Heden, Watemexoted, and Cheekepuehat formalized the transfer of their land to thirteen of the undertakers, including Edmund Farrington. In exchange they received sixteen coats, three-score (60) bushels of Indian corn, and a promise of protection against more warlike mainland tribes. One of the witnesses who signed the deed was Robert Terry, who moved to Flushing in 1642 and married Thomas’ sister Sarah Farrington. Before the winter of 1640/1, around 40 households had arrived, most living in makeshift “cellars” with sod roofs. Thomas’s brother Edward Farrington must have also joined the family there, for he is named in the town records of 1644.

However, the Farringtons did not linger there. Edmund returned to Lynn before May 1643, when a Southampton resident named John Cooper was granted “the lott of Goodman Farrington,” having fenced the plot on his behalf, and being still owed 15 shillings for his labor. (Fencing carried a near-existential importance to early Colonial farmers in the wilderness, and early court records abound with neglected fences.) John also rejoined their father in Lynn. No Farringtons appear on the 1644 roster for a whale-watching patrol compulsory for males over age 16. By 1645 Thomas and Edward owed five pounds to the town, which in an echo of The Scarlet Letter’s famous opening lines, the fledgling town earmarked for a jail. However, Southampton land records indicate that the family kept a footprint there in absentia for at least two decades, with references such as “the land between the ffaringtons and the Pond” (1653); they were further memorialized in old place names like “Farrington’s Pond” (Old Town Pond), “Farrington’s Point” (Noyack), and the contemporary “Farrington Close,” site of a condominium development.

“The founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue and happiness they might originally project, have invariably recognized it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne - The Scarlet Letter

The Old Towne Pond: “…ye pond commonly called Farrington’s Pond, ranging on the old side of towne.”

George Bradford Brainerd. East Side of Pond, South Hampton, Long Island, ca. 1872–1887. (Image: Brooklyn Museum)

It’s unclear exactly when or why Thomas made his way to the Dutch instead of rejoining his family in Lynn, especially given New Netherland Director Kieft’s ongoing wars with the Indians, and John Farrington’s recent brush with the authorities there. Certainly hardships and constraints were written into the founding documents of Southampton: no resident was allowed more than four acres for a home lot and twelve for planting, and Farrett’s patent permitted just one designated resident to barter with the Indians, and then only for foodstuffs, as Lord Stirling maintained a monopoly on trade. In 1643 tensions flared with the previously friendly Indians, when Lieut. Howe (one-time vandalizer of the Dutch Arms) fatally knifed a Native man suspected of murdering an Englishman. On another note, if Thomas had received news from his hometown in late 1643, he might have heard about the Battle of Olney Bridge, where outnumbered Parliamentarians loyal to Oliver Cromwell turned back the Royalist forces, some at the cost of their lives. Perhaps the religious tolerance of the Dutch seemed appealing against this backdrop of sectarian strife. Whatever the story, both Edward and Sarah Farrington eventually followed Thomas to Flushing, while their parents and their three youngest siblings- John, Mathew, and Elizabeth- remained at Lynn under the governance of Governor Winthrop.

Thomas married Helena Applegate, the daughter of fellow Flushing patentee Thomas Applegate, on an unrecorded date. Their only son, Thomas Farrington, Jr., was baptized on April 30, 1645 in the Dutch Reformed Church of New Amsterdam (which spelled their name “Pharendon.”) Although the Church did offer the sacraments of marriage and baptisms to members and non-members alike, this choice suggests that the couple did not hold any strong objections to the Reformed faith. They may have belonged to one of the English denominations, such as Congregationalist or Presbyterian, whose strict Calvinist beliefs were considered “Reformed” by the Dutch. The Church records next reveal that on August 15th, 1646, Helena “widow of Thomas Farrington” married Lovis Hulot (Lewis Hewlett.) Although we do not know his date of death, Thomas would have been no more than thirty-two years old.

Helena is one of the few “Founding Mothers” on whom we have even bare biographical data. We know that within 18 months her second husband also died, leaving her with a second fatherless child. Helena then married Charles Morgan, a former soldier of the Dutch West India Company, and had four more children with him. She died in 1652 at the age of 31, orphaning Thomas Farrington, Jr.. In 1654 Thomas Applegate, “as grandfather of the surviving child of Thomas Farrington,” sued his grandson’s conservator William Harck, demanding he account for “the goods and cattle, which he as curator of said child has in his possession." (Harck appeared in our profile of Thomas Saul, as the provisional Sheriff of Flushing who was “thrown upon the ground” while attempting an arrest, and later dismissed for performing an illegal marriage and allowing it to be consummated in his bed.) The outcome of the suit was not recorded, but in 1669 Thomas Jr. sold land he owned in Gravesend, where his grandfather Applegate had lived. He signed the deed with a mark; the family had gone from illiteracy to literacy and back within three generations. Thomas married but was widowed young, and moved to Westchester with his only daughter. There is no record of him ever remarrying or having more children. The male line of Thomas Farrington had died out.

Meanwhile, his brother Edward Farrington thrived in Flushing, where he raised four sons, one of whom carried on the name of Thomas. Edward and his descendants were important enough to the town, and to the Bowne family, that we will devote a follow-up post to him and selected other members of the family.

Our research is a work in progress. If you have additional information on the Flushing Charter signers, or believe that you may be a descendant, we would like to hear from you! You can write to us at office@bownehouse.org