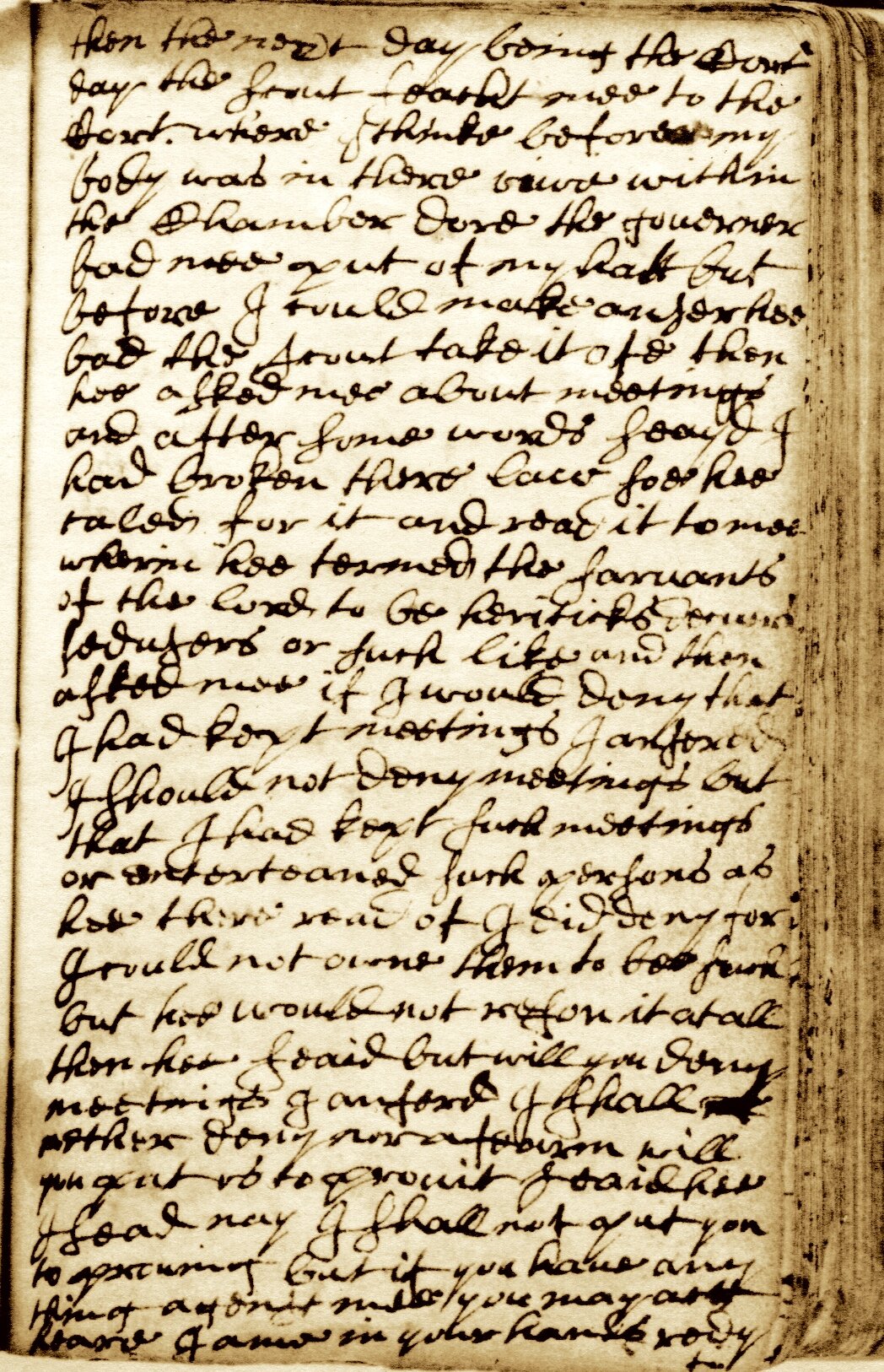

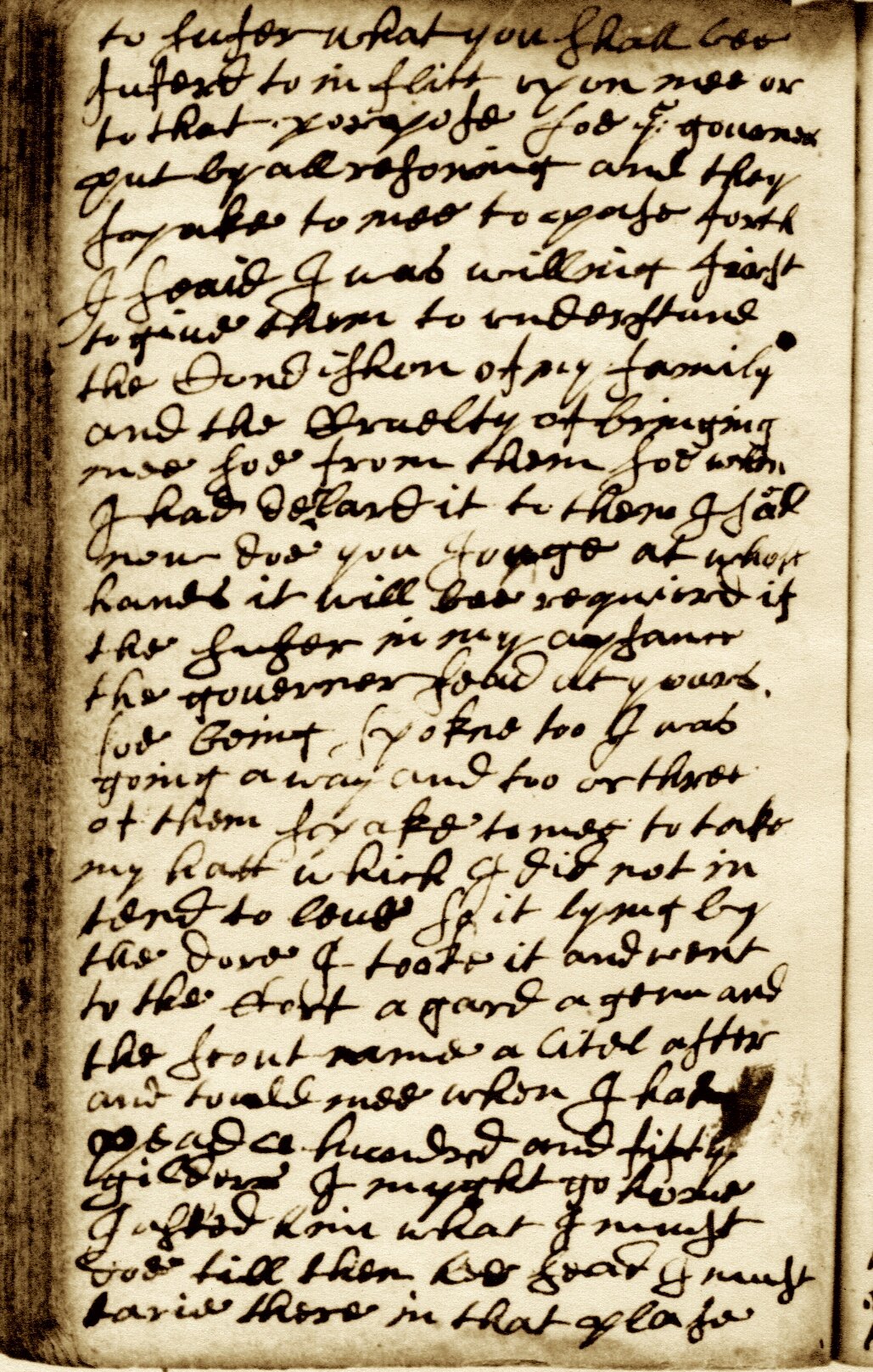

JOURNAL OF JOHN BOWNE: FOLIO 50, recto & verso (front and back)

—Continued from September 13, 1662- Bowne at Fort Amsterdam

“Then the next day being the Court day, the Scout fetched me to the Court, where I think before my body was in their view within the Chamber door the Governor bade me put off my hat, but before I could make answer he bade the Scout take it off. Then he asked me about meetings, and after some words said I had broken the law. So he called for it and read it to me, wherein he termed the servants of the Lord to be heretics, deceivers, seducers, or such like…”

“…and then asked me if I would deny that I kept meetings. I answered I should not deny meetings, but that I had kept such meetings or entertained such persons as he there read of, I did deny, for I could not own them to be such. But he would not reason it at all. Then he said, but will you deny meetings? I answered, I shall neither deny nor affirm. - Will you put us to prove it? said he. I said nay, I shall not put you to proving, but if you have anything against me you may act: here I am in your hands, ready to suffer what you shall be suffered to inflict upon me, or [something] to that purpose. So the Governor put by all reasoning, and they spake to me to pass forth. I said I was willing first to give them to understand the Condition of my family and the Cruelty of bringing me so from them. So when I had declared it to them I said, Now do you Judge at whose hands it will be required if they suffer in my absence. The governor said: At yours. So being spoken to, I was going away and two or three of them spake to me to take my hat, which I did not intend to leave, so it lying by the door I took it and went to the Cort a gard again, and the Scout came and told me when I had paid a hundred and fifty guilders I might go home. I asked him what I must do till then. He said I must tarry there in that place.”

To be continued on September 15, 1662

Illustration from Scribner’s Magazine.

Portrait of Director Peter Stuyvesant. Attrib. Hendrick Couturier, circa 1663. (NY Historical Society)

the Court: The Court consisted of the Director and Council of New Netherland. It heard serious criminal cases, civil cases for large amounts of money, and appeals. Bowne does not mention the presence of the Council, although they presumably were in attendance. The accused is not supplied with a lawyer, nor does he ask for one. No witnesses are called by either side. The sentence is pronounced after Bowne’s dismissal from the courtroom and relayed to him by the Schout.

put off my hat: doff his hat in deference to the Court. Quakers believed that the “hat honor” was idolatrous and refused on principle.

the law: The ordinance against Quakers has not survived. Stuyvesant may be reading from a 1656 law against “conventicles,” which predated the Quaker presence in the colony. This ordinance simply restated New Netherland’s long-standing but unevenly observed ban on all religious meetings outside the Reformed Church, and on preaching by “unqualified” persons.

seducers: refers to spiritual, not physical, seduction by unorthodox preachers with attractive yet forbidden ideas

“at whose hands it will be required”: who will bear the blame; who will be held to account

Cort a gard: a term Bowne uses for “jailhouse”

a hundred and fifty guilders: 25 pounds Flemish, the standard fine for attending conventicles.

This scene marks Bowne’s second attempt at defending himself, the first being his protest to Resolved Waldron the Schout at the time of his arrest, when he pointed out that the warrant referred to “people taken in meetings,” and Waldron “found me in none.” At this stage of the proceedings, Bowne does not refer to the Charter or Patent of Flushing, which promised liberty of conscience. Instead, he tries another legalistic strategy: that while he has attended conventicles, they do not involve the “heretics, deceivers and seducers” that the language of the ordinance refers to. Therefore, he is not guilty of any offense. He may have violated the letter of the law by hosting a conventicle outside the Reformed Church, but not the spirit, as Quakers are true Christians and pose no threat to the community. To Stuyvesant, this distinction is sophistry. He asks Bowne point-blank if he admits to “meetings”, shorn of any modifiers that might invite argument. Having already said “I should not deny meetings,” Bowne now resorts to stonewalling, refusing to either confirm or deny his participation. He knows that the government’s case is weak, as the evidence against him is hearsay, and there are no witnesses present. However, when Stuyvesant asks if Bowne is going to make him prove the case, Bowne demurs and demands that the Court judge him on the facts at hand. Maybe he hopes that the Court will drop a weak case to spare themselves the work of proving it; conversely, maybe he suspects that the outcome is predetermined. Stuyvesant “puts aside all reason” and dismisses him, having heard quite enough. Bowne finally makes a last-ditch emotional appeal to the Court, pleading with them to consider the sufferings of his family. Unmoved, Stuyvesant fires back that Bowne himself is to blame for their suffering.

Bowne is so rattled by this reception that he almost leaves without his hat and has to be handed it by the soldiers who took it from him. The matter of the hat no doubt disposed Stuyvesant against him before he ever entered the courtroom. Following the incident the day before, The Director-General gave Bowne no chance to deny him the “hat honor,” the respectful doffing of the hat in the presence of authority figures or one’s social superiors. Indeed, Bowne was fortunate that Stuyvesant confined his reaction to forcibly stripping him of his headwear. Quakers in England were routinely fined, imprisoned, beaten, and in a few cases even killed for refusing to observe this formality in the courtroom. Often this secondary offense took precedence over the actual crime or misdemeanor that brought them before the court in the first place.

The scholar Susan Wareham Watkins writes that due to the extreme reaction that this particular breach of etiquette provoked, refusing the hat honor served as an initiation rite for recent Quaker converts. It set them apart from the rest of the community and thus cemented their new-found group identity. By courting persecution and suffering for their beliefs, they became more invested in their spiritual journey. Meanwhile, their status was correspondingly elevated among more established Quakers. Thus Bowne willingly embraced the confrontation over his broad-brimmed felt Quaker hat, even knowing that it would damage his chances of a favorable verdict. It was the first public step on a longer spiritual journey.

Next: September 15, 1662- John Bowne is delivered his Sentence.

REFERENCES

Watkins, Susan Wareham. Hat Honour, Self-Identity and Commitment in Early Quakerism. Quaker History, Vol. 103, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 1-16