Edward Farrington, while not himself a Flushing Charter signer like his brother Thomas, was a prominent member of the community who amply deserves the title of honorary founder. Although his early life remains the most enigmatic of all the Farringtons, it was Edward’s later career in Flushing that established the family alongside the Bownes as one of the town’s important Quaker lines for generations to come.

Edward Farrington’s childhood hometown of Olney, Buckinghamshire. The bridge shown was the site of the 1645 Battle of Olney Bridge, a skirmish in the English Civil War.

Like Thomas Farrington, Edward was born to Edmund Farrington and Elizabeth Newhall, probably in the village of Sherington in Buckinghamshire, England, and later moved with his family to the nearby town of Olney. His birthdate has been estimated around 1615. Neither Thomas nor Edward accompanied the rest of the family to the Bay Colony in 1635 on the ship Hopewell; as young adults they may have been indentured or apprenticed at the time. Edward first appeared in the Colonial records in March 1644/5. The early records of Southampton, the first English settlement on Long Island, show that as of that date he and Thomas owed 5 pounds to the town. Unlike his brother, Edward was not an original incorporator there, and his residency must have been brief, as his name does not appear on any of the other early town lists. Nor does he figure in the court records of Lynn, Massachusetts, where his parents and several of his siblings lived. Of course, it is possible that he did live there, but never had any business before the court.

The timing and reasons for his eventual move to Flushing are just as obscure. Possibly he inherited some of his brother’s land after Thomas’s untimely death in 1645 or 1646. Alternatively, his brother-in-law Robert Terry, who settled in New Netherland in 1643 and married Sarah Farrington, may have recruited him to the colony. We do know that Edward arrived in Flushing by 1651, when he married John Bowne’s sister Dorothy and brought his new brother-in-law to visit the town.

“As I remember, I came to vlishing [Flushing] the fifteenth day of the 4 month caled June Ould Style 1651 with my Brother Edward ffarington.”

- John Bowne’s Journal (1650-1694)

Bowne’s Journal does not describe how Edward and Dorothy met, but the Bownes had previously lived in Boston, not far from Edward’s family in Lynn.

Edward was soon nominated by the townsfolk for the office of Flushing magistrate, and Director Stuyvesant then selected him from among the nominees. Evidently he enjoyed a good reputation with his fellow citizens and the Dutch authorities alike. He was sworn in on April 22, 1655, with William Lawrence (profile to come) and Thomas Saul, both Flushing Charter signers. He was re-appointed on March 25, 1656, this time alongside Lawrence and William Noble. However, religious disputes soon brought the magistrates into conflict with the man who had appointed them. Around November 1656, Farrington and the other two magistrates headed a petition of the residents of Flushing for the release of their Schout, or Sheriff, William Hallett. Hallett (who coincidentally happened to be Hannah Bowne’s stepfather) had been arrested for allowing a Baptist preacher from Rhode Island to hold “conventicles,” or unauthorized worship services, in his house. The petition on Hallett’s behalf was conciliatory in tone, simply pleading ignorance of any wrongdoing on his part. He was released after begging pardon, incurring a hefty fine, and surrendering his office. However, the next protest from Flushing would prove more defiant.

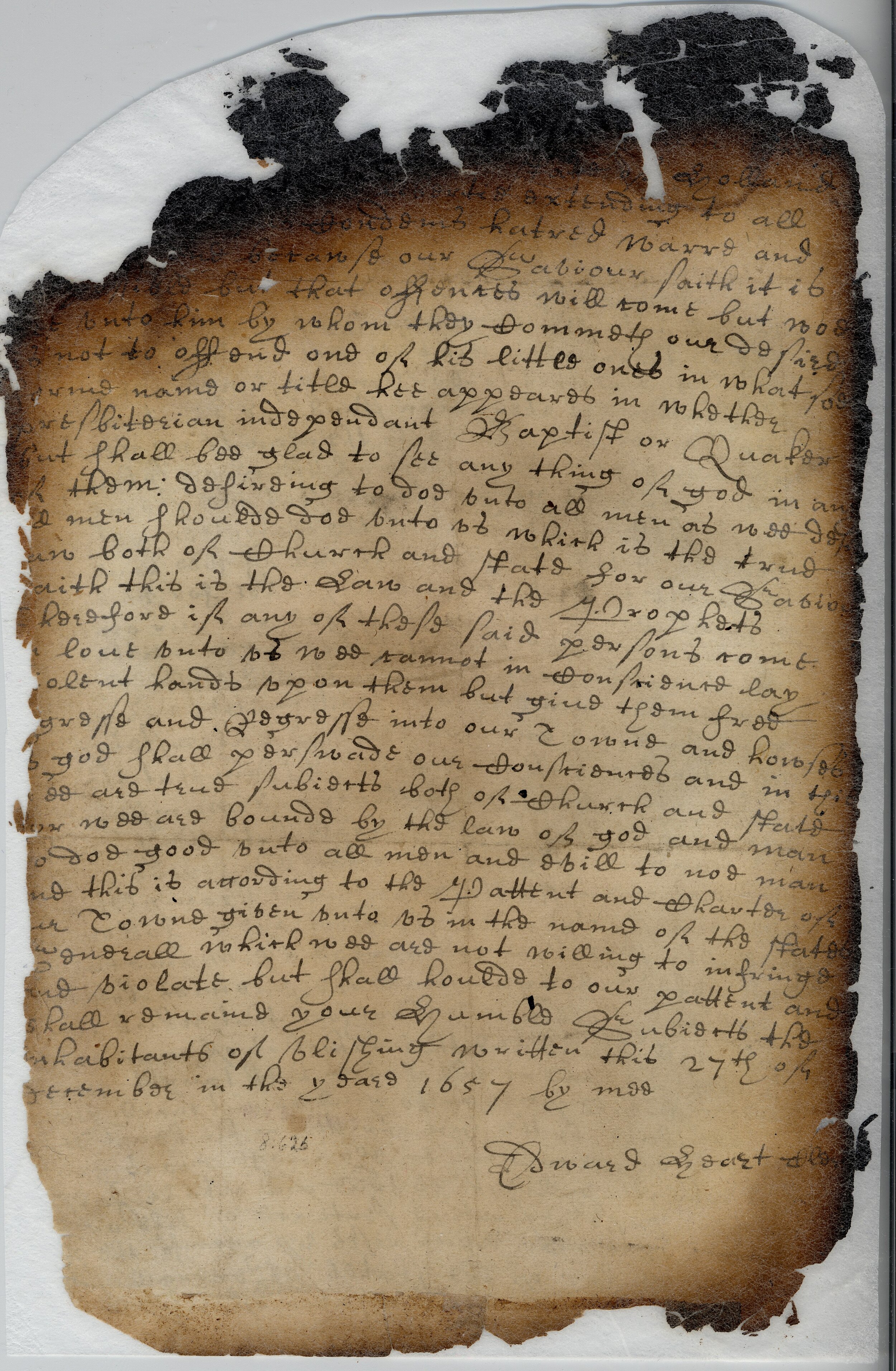

Edward Farrington was still serving as magistrate on December 27, 1657, when he joined the 30 people who signed the Flushing Remonstrance at a town meeting. The Remonstrance was a formal protest against Director Stuyvesant’s recently posted bans on Quakers in the colony. Today this document, preserved in the New York State Archives, is recognized as one of the first principled expressions of support for religious pluralism in the New World. The signers proclaimed that to persecute Quakers violated not only their moral code, but also their Town Charter, which promised “liberty of conscience”:

“Therefore if any of these said persons* come in love unto us, we cannot in conscience lay violent hands upon them, but give them free egresse and regresse unto our Town, and houses, as God shall persuade our consciences, for we are bounde by the law of God and man to doe good unto all men and evil to noe man. And this is according to the patent and charter of our Towne, given unto us in the name of the States General, which we are not willing to infringe, and violate, but shall houlde to our patent and shall remaine, your humble subjects, the inhabitants of Vlishing.”

- from the Flushing Remonstrance, 1657

* “one of [God’s] little ones, in whatsoever form, name or title he appears in, whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker…”

[READ THE FULL TEXT OF THE FLUSHING REMONSTRANCE]

Stuyvesant perceived these sentiments as subversion. He ordered the arrest of all four officers of the town who had signed: Farrington, his fellow magistrate William Noble, town clerk Edward Hart, and Tobias Feake, the new Schout who had hand-delivered the Remonstrance to the Director. (Feake happened to be Hannah Bowne’s first cousin- she seems to have been surrounded by heterodox menfolk.) Farrington’s role in drafting the Remonstrance is unclear, and may have been limited to signing it. Under interrogation, town clerk Edward Hart claimed that he had simply summarized the collective sentiment of all the Flushing residents who had spoken out on the issue, and could not attribute its wording to any particular individual. He admitted that he had previewed the text to Farrington, Noble, and Feake before reading it at the town meeting, but could not say if they approved it. Despite Hart’s stonewalling, the local officials were held personally accountable for the conduct of all 30 signers in their jurisdiction. The records of the Council of New Netherland document Farrington and Noble’s ensuing encounter with the legal system.

“The Old Stadt Huys of New Amsterdam.” Historic Postcard Collection (New York Pulic Library) The Town Hall, a former tavern turned courthouse, where prisoners were often kept awaiting trial.

On January 1, 1658, the two magistrates were summoned before the Director and Council of New Netherland and arrested. The transcript of their interrogation before the commies [commissioners] does not survive, but according to their sentencing recommendation both men blamed the highest-ranking official, Schout Tobias Feake, for leading them astray. This mollified the authorities enough to grant their petition of January 8 to be given the liberty of Manhattan while awaiting sentencing.

On January 9, Farrington and Noble jointly submitted their official response to the charges, in which they “confessed themselves not guiltie…jest ignorant.” Their plea to “the Noble and Reverent Lords, the Director and Council” downplays the Remonstrance as merely an opinion offered to the Director for his approval. The writers profess ignorance of the anti-conventicle acts- except for Stuyvesant’s anti-Quaker ordinances, which they (quite improbably) purport to have faithfully enforced- and further claim unfamiliarity with “the Articles which the Fiscael [public prosecutor Nicholas de Sille] is pleased to call our Charter.” Then there follows a mild, yet unmistakable, rebuke: the magistrates note that they have however read their Patent, which they call their Charter, and believe it guarantees “liberty of Conscience: without molestation either of magistrate or minister.” They challenge Stuyvesant to correct them on this point if they have misunderstood, signing off as his “humble servants.” Notably, William Noble’s mark stands in for his signature, indicating he could not write. Apparently, there was no literacy requirement for magistrates in New Netherland. This fact suggests that Farrington probably took the lead in composing the letter, especially as he was the more senior magistrate of the two.

Edward Farrington and William Noble, Response to the Court. January, 9, 1658. (New York State Archives) View and download in hi-res

Even this mild response may have struck too defiant a note, because on January 10, the very next day, the two magistrates submitted a second, briefer petition in which they admitted error, begged pardon, and promised to give no further offense. Following their repentance and their fingering of Tobias Feake as the ringleader, Farrington and Noble were sentenced to court costs only, and released. The Council’s leniency also reflected their suspicions that Farrington had been influenced by Henry Townsend, another original Flushing patentee who had been arrested for harboring Quakers in neighboring Rustdorp (Jamaica) the previous September. Indignation over Townsend’s case almost certainly helped to inspire the Remonstrance. However, when questioned before the Council Townsend only admitted to visiting Farrington as an old acquaintance, and denied persuading him to sign the Remonstrance.

After their release, Farrington and Noble felt unsure whether they could return to the bench, despite the growing backlog of cases before the court. Their senior colleague, William Lawrence, wrote to Stuyvesant: “Edward Farrintton and William Nobell in regard of ther latte trubelle are nott willing to proseed aney ferrder withoutte your honeres forder order.” Stuyvesant’s “forder order” was to suspend the court in Flushing until March 26, when he issued an edict restructuring the town government. He named William Lawrence (who had not signed the Remonstrance) as a temporary replacement for the disgraced Schout, and eventually appointed a town Constable instead, a lesser office lacking prosecutorial powers. He also banned most town meetings, which were the preferred organ of decision-making for the English settlers, instead creating an advisory board of seven politically reliable citizens whom he would personally approve. Farrington and Noble were, however, allowed to resume their duties as magistrates, and indeed were repeatedly reappointed. Despite their reinstatement, their previous act of defiance had cost the town much of its cherished autonomy.

Letter, November 5th/15th, 1662. John Bowne in jail at New Amsterdam to Hannah Bowne in Flushing. Describes farm labor Edward Farrington, aka “Brother John,” should assist with in Bowne’s absence. (Bowne Family Papers of Flushing, Long Island. Bowne House Archives.)

Although none of the Remonstrance signers publicly identified as Quakers in 1657, Edward and Dorothy did later join the Religious Society of Friends, probably around the same time as John and Hannah Bowne. Farrington’s retirement or removal from the office of magistrate in 1662, when he was replaced by the apparently rehabilitated former Baptist sympathizer William Hallett, may provide a hint as to his date of conversion. Quakers did not believe in taking oaths, so after his “convincement” he could not have been sworn in for a new term. Of course, this was around the same time that John and Hannah Bowne began holding meetings in the Bowne House. John and Hannah were close to Edward, whom they referred to as “Brother John” or “Brother Farrington.” During his imprisonment in the Fall of 1662, Bowne advised Hannah to enlist Edward for the heavy labor he would normally have done on the farm, including helping with the haying and, “when he is not about other needful work...either providing firewood for winter or a-clearing in the new ground.” During his exile, John recruited an indentured servant named James Clement and sent him to Flushing to help out, but upon having second thoughts wrote home: “If he be heady, put him to Brother Farrington.”

Edward lived in Flushing for the remainder of his life. He appears on the 1666 Patent for Flushing issued by Governor Nicolls after the English takeover. In 1667, his father Edmund wrote a will leaving him and his brother-in-law Robert Terry each twenty shillings. (The bulk of the paternal estate went to the siblings who had remained in Lynn.) Edward raised four sons with Dorothy, named after himself and his three brothers: John, Edward, Thomas, and Mathew. (The fact that he named his firstborn John, rather than Edward Jr., may hint at his great regard for his brother-in-law, John Bowne.) Genealogies also record three daughters: Dorothy, Mary, and Margaret, although little is known of them. Edward seems to have prospered in Flushing and become a substantial landowner before his death around age 60. His will was probated on July 1, 1675, when his widow was granted letters of administration. Most of his estate went to John. Younger sons Edward and Thomas received 50 acres each plus a share of meadow, while Mathew received 20 acres and three meadows. His daughters either predeceased him or were omitted from the inheritance.

The following year John Bowne wrote to his wife, then traveling in England: “I must acquaint you to thy grief, as it has been to mine, that my sister did take a husband yesterday. It was the man who went and came with L[ewis] Morris to the New Countries with us.” (It is not clear from this description who the new husband was; Lewis Morris was a Quaker based in the English colony of Barbados who undertook religious visits to New England, while the “New Countries” may have referred to New Jersey or Pennsylvania.) According to family historian Jacob Titus Bowne, Dorothy was censured and expelled from the Flushing Quaker Meeting for “outmarriage,” or marrying a non-Quaker. However, this second marriage may have ended before her death, because on June 24, 1678, Letters of Administration were granted to her son John for “Dorothy Farrington, widow & relict of Edward Farrington.” The matter poses a bit of a mystery. Regardless, the Farringtons remained an influential family in both the Quaker Meeting and the town of Flushing well into the 19th century.

Our research is a work in progress. If you have additional information on the Flushing Charter signers, are a descendant, or just believe that you may be a descendant, we would like to hear from you! You can write to us at bownehouseoffice@gmail.com