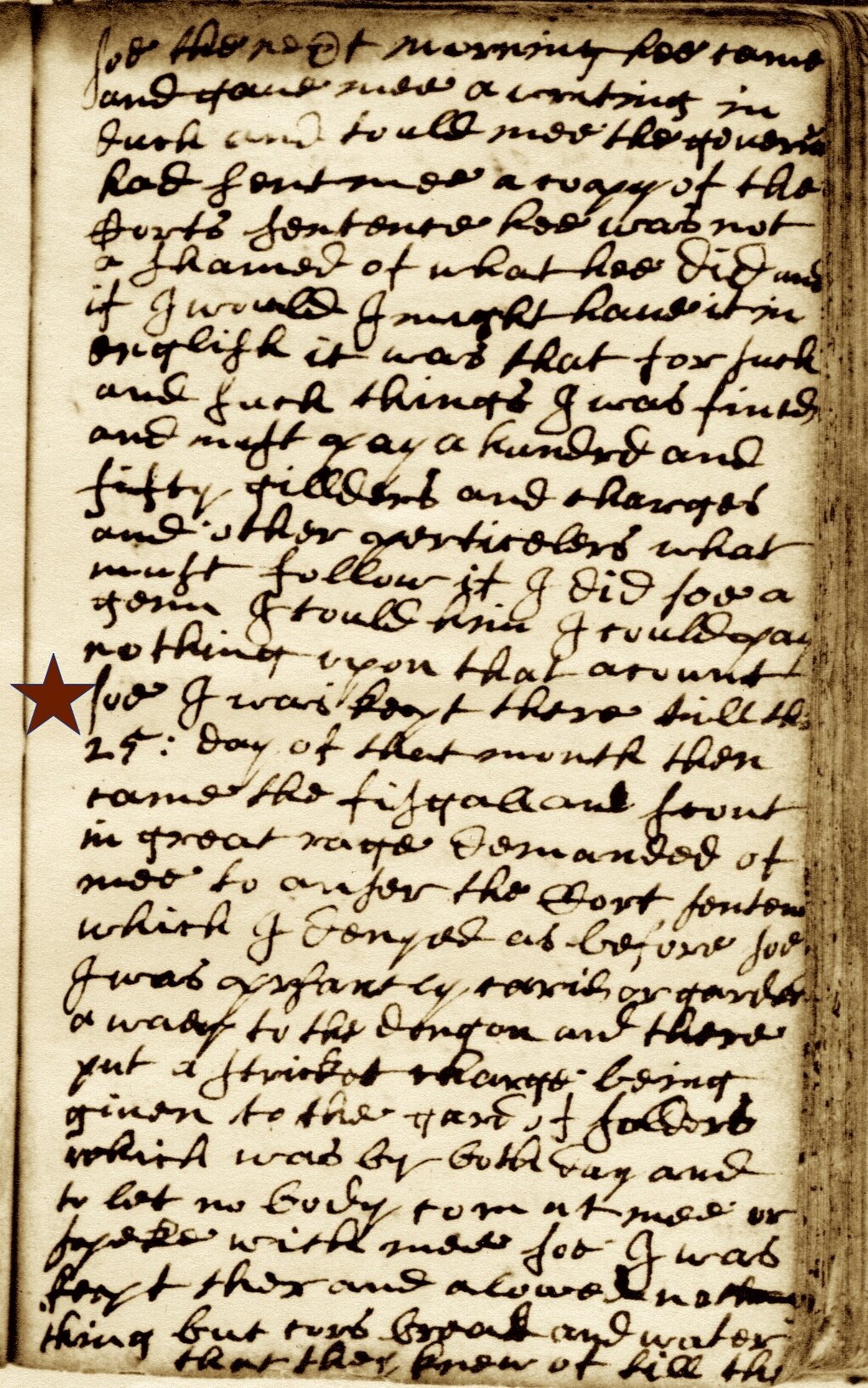

JOURNAL OF JOHN BOWNE, FOLIO 51

Previous post: September 21, 1662- Ordinance Against Conventicles

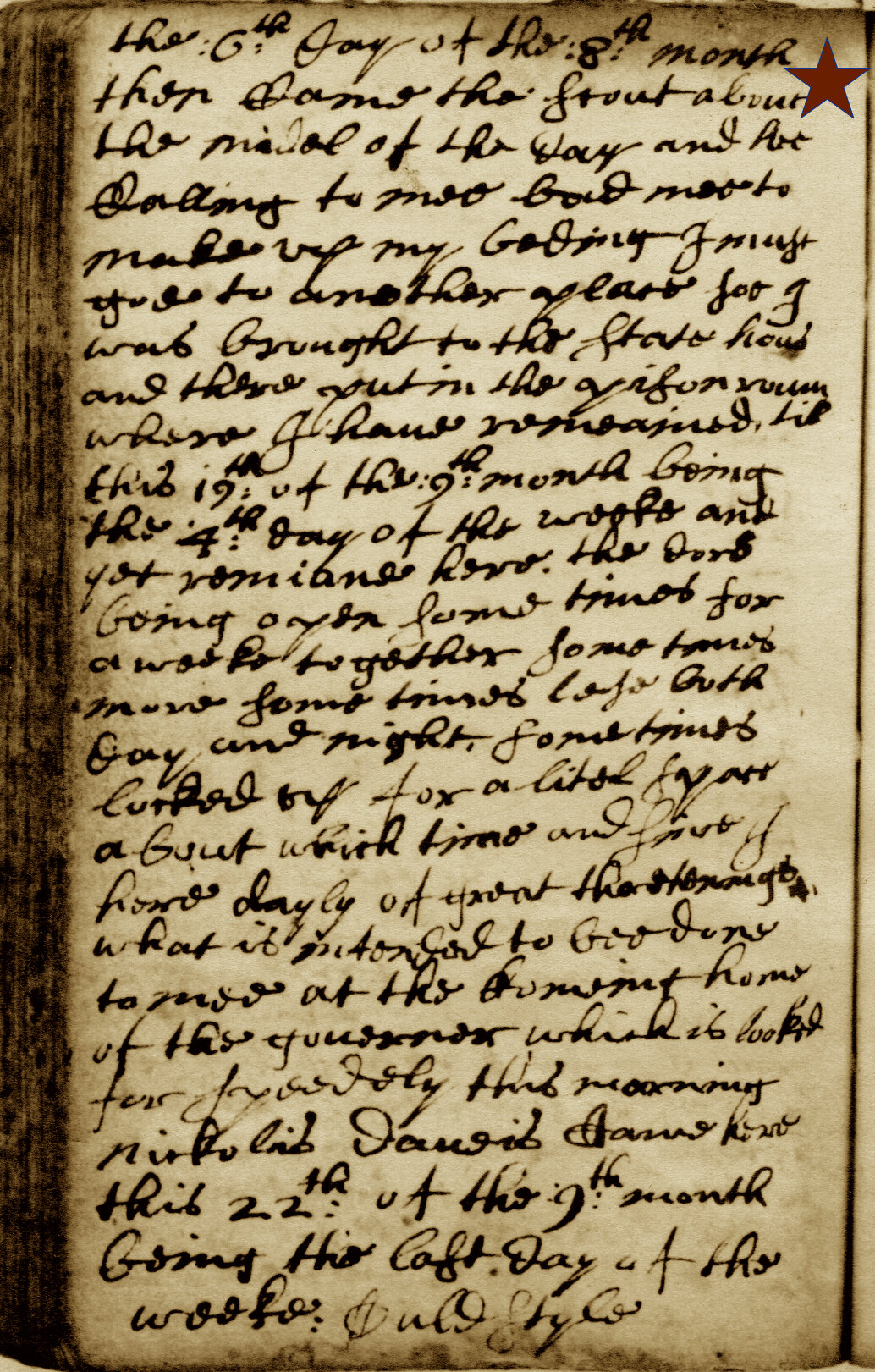

“[...so I was kept there till the 25 day of that month.] Then came the Fiscal and Scout in great rage. [They] demanded of me to answer the Court sentence, which I denied as before. So I was presently carried or guarded away to the dungeon and there put, a strict charge being given to the guard of soldiers, which was by both day and [night] to let nobody come at me or speak with me. So I was kept there and allowed nothing but coarse bread and water than they knew of ‘till the 6th day of the 8th month.”

(Red stars marks the beginning & end of today’s passage.)

Notes on the Text

“the 25th day of that month”: the 25th of September in the old calendar used by John Bowne and other English subjects (October 5th New Style)

“the Fiscal and Scout”: The Fiscal, or public prosecutor, of New Netherland in 1662 was Nicholas de Sille. The Provincial Schout, or Sheriff, was named Peter Tonneman, although here Bowne may actually be referring to Deputy Schout Resolved Waldron, the Anglo-Dutch officer who had arrested him. These men’s salaries were partially funded by the fines that they collected, which no doubt contributed to their “great rage” at Bowne for refusing to pay.

the Court sentence: Bowne had been found guilty of violating the Ordinance against Conventicles, and been issued a fine of 150 guilders, or 25 pounds Flemish.

the dungeon: Until this point, Bowne had been confined in what he calls “the cort-a-gard.” It is unclear exactly what this term refers to, but it may have been a cell adjoining the sentry box or the barracks at Fort Amsterdam. The “dungeon” was presumably also located in the Fort, as the only alternative place of detention in New Amsterdam was the Stadt Huys, or City Hall, where Bowne was not moved until the following month. The word calls to mind the account of Robert Hodgson, who was nearly martyred by Stuyvesant following his 1657 arrival on the Woodhouse, which brought the first Quakers to New Netherland: “I was cast into a dungeon, so odious as I never saw, for wet, dirt, and nasty stink.” The move clearly marks an escalation in the pressure campaign against Bowne.

“…that they knew of”: One of the mysteries of Bowne’s imprisonment is how he managed to survive and remain healthy on a bread and water diet. Here, Bowne hints that, in fact, he did not have to. In fact, a separate page towards the back of Bowne’s journal, where he sometimes jotted down accounts and memoranda, reveals that Bowne had a relationship with an English couple who owned a nearby tavern, and that they were able to smuggle provisions to him. We will explore this arrangement further in a separate post at a later date, as Bowne remained a customer of theirs throughout the Fall. (Bowne’s aside also suggests that he was not overly worried about his captors reading his diary.)

Sentencing of the Tiltons and the Spicers

On the same day that Bowne was remanded to the dungeon, the four Quakers from Gravesend who had been arrested around the same time as he were sentenced. These were the Tiltons, a middle-aged married couple, and the Spicers, a widow and her adult son. As all were repeat offenders who had been arrested in past years, the Tiltons and the Spicers were not given the same opportunity as Bowne to mend their ways. The fire-damaged sentencing records appear below, courtesy of the New York State Archives. (Fortunately, translations commissioned by Governor DeWitt Clinton before the fire have survived.)

Sentence of John and Mary Tilton of Gravesend. October 5, 1662, Dutch Colonial Council Minutes, 1638-1665. (New York State Archives.) View and download in hi-res

Sentence of Michelle and Samuel Spicer of Gravesend. October 5, 1662. Dutch Colonial Council Minutes, 1638-1665. (New York State Archives.) View and download in hi-res

Interestingly, only the Tiltons’ sentence contains an order in English. John Tilton was also the sole member of the Gravesend group who had insisted on received a written copy of the complaint against him from the Notary Public. He had served as Town Clerk in Gravesend for many years; possibly this role had given him an appreciation for the importance of getting things on the record.

Council Resolution re: Sentence of John and Mary Tilton

“Presented and read the conclusion of the Attorney-General versus John Tilton and his wife, and the frivolous and obstinate answers of the defendants,—so was adopted the following resolution:

[In Dutch] Whereas Director-General and Council are certainly informed, and actually find it so, that John Tilton, and so too, his wife, residing at Gravesend, continue yet pervicacious and obstinate in entertaining and lodging the Quakers, and frequenting their conventicles, notwithstanding the aforesaid Tilton was for it, in the year 1658, on the 10th January, condemned to a fine, and since, in the year 1661, on the 20th January, was commanded to leave this province, but has so far conspired, in the hope of his reformation; but whereas he, as it is already said continued obstinate, so it is resolved and deemed necessary, to avoid, as far as possible, confusion and schism in this youthful province, to banish the aforesaid John Tilton and his wife out of this province.

[In English] The Governor-General* and Council of New Netherlands do ordain and command you, John Tilton, with Mary Tilton your wife, to depart and remove out of this province before the 20th day of November next ensuing, upon pain of corporal punishment. This enacted and ordained, in our assembly kept in Fort Amsterdam, the 5th October, 1662: _____"

*Stuyvesant’s title was actually Director-General; Governor-General was a higher rank reserved for administrators of larger, more important colonies. However, the English residents (such as the English Secretary, who would have written this addendum) may not have been fully aware of the distinction.

Council Resolution re: Sentence of Michelle and Samuel Spicer

“1662: 5th October.___Whereas the Director-General and Council in New Netherland are certainly informed, and found it actually to be so at different times, that those of the sect called Quakers keep an unusual correspondence, and are continually supported, kindly received and lodged at the House of Michel Spicer, residing at s’Gravesende,* now a prisoner: she, with her son Samuel Spicer, before more than once have been arrested and fined, with an express warning to be on their guard in the future, and avoid it, on the penalty of banishment, nevertheless they thus far continue in this with great obstinacy; but what is more, lately dared to distribute and spread seditious and seducing pamphlets among the inhabitants of this province, to propagate the aforesaid heretical sect of Quakers: wherefore, it being necessary, to avoid confusion and schisms in thi new-rising province, to crush this abominable sect of Quakers, who aim at nothing else but to bring the word of God, religion, and government into disrespect, so is it, but the Director-General and Council, resolved to keep all others under a better control in this province.

The Director-General and Council in New Netherlands command you, Michel Spicer, that ye shall depart from this province, with your son Samuel Spicer, before the 20th November next, on the penalty of corporal punishment.

Done and commanded, in our meeting in Fort Amsterdam, in New Netherlands, on the day as above.”

Notably, the prisoners were given a generous amount of time to get their affairs in order before leaving the province- despite the fact that John Tilton had simply ignored a previous sentence of banishment. Later records show that the Quakers did not, in fact, leave the colony; in fact, the following May, Stuyvesant was still trying to remove them. Shortly thereafter, the Dutch effectively lost administrative control of the English towns in New Netherland, due to the maneuverings of neighboring Connecticut, which was aggressively asserting the English claim to all of Long Island. Samuel Spicer was living in Gravesend as late as the 1680s. The Tiltons also resided there for the rest of their lives. While Stuyvesant had autocratic tendencies, the thinly-stretched administrative and police state available to him simply lacked the capacity to enforce them out on Long Island.