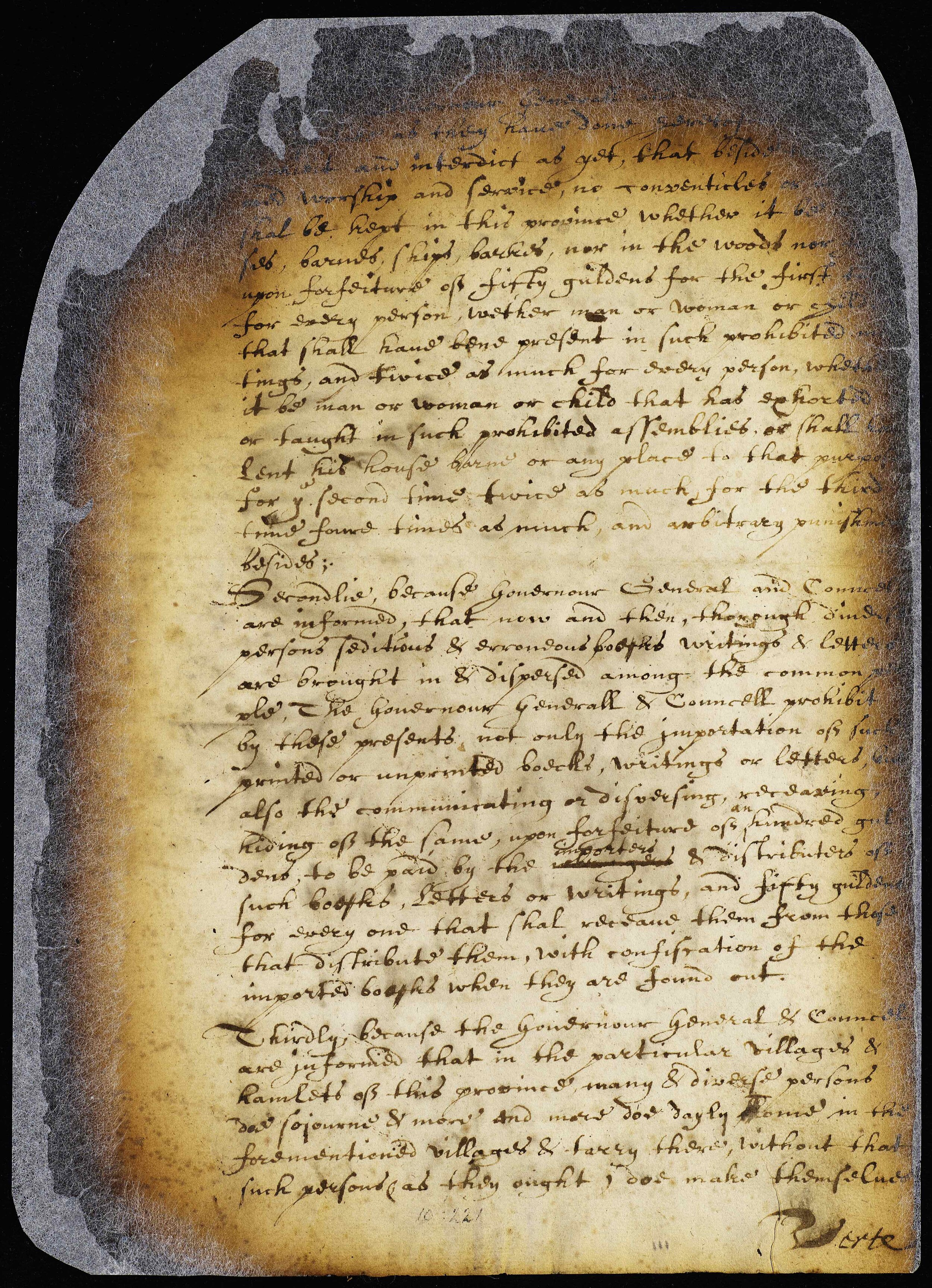

First, the Governor Generall and Councell forementioned, Like as they have done heretofore, so they prohibit and interdict as yet, that beside the Reformed worship and service, no Conventicles or meetings shal[l] be kept in this province whether it be in houses, barnes, ships, barkes, nor in the Woods nor fields, upon forfeiture of fifty guldens for the first time for every person whether man or woman or child, that shall have been present in such prohibited meetings, and twice as much for every person, whether it be man or woman or child that has exhorted or taught in such prohibited assemblies, or shall have lent his house barne or any place to that purpose; for ye second time twice as much; for the third time foure times as much, and arbitrary punishment besides.

Secondlie, because Governour General and Councel are informed, that now and then, through diverse persons seditious and erroneous boecks [books] writings & letters are brought in & dispersed among the Common people, The Governour Generall and Councell prohibit by these presents not only the importation of such printed or unprinted boecks, writings or letters, but also the communicating or dispersing, receaving, hiding of the same, upon forfeiture of an hundred guldens, to be paid by the importers and distributers of such boecks, letters or writings and fifty guldens for every one that shal[l] receave them from those that distribute them, with confiscation of the important boecks when they are found out.

Thirdly, because the Governour General & Councel are informed that in the particular Villages and hamlets of this province many & diverse persons doe sojourne & more and more doe dayly come in the forementioned Villages and tarry there, without that such persons (as they ought) doe make themselves knowne & shew from whence they came & to what end, or that they (as other inhabitants) doe performe the oath of fidelity, the Governor General and Councel doe ordaine & command by these presents dat [sic] al[l] and every particular person, that in the same manner beforementioned, without Leave and foreknowledge of the Governour Generall and Councell are come within this province & have not performed the Oath of fidelity shall within the tyme of six weekes come to ye office of the Secretary of the Governour Generall & Councell that their names may be regist’red and may performe the oath of fidelity like as other inhabitants & to subscribe it, upon forfeiture of fifty guldens & arbitrary punishment besides.

And to prevent in the future such disorder & prohibited assemblies the Governour General & Councell forementioned doe ordaine & command all Magistrates, Schouts, Marishals, Officers & Commanders within this province to obey & execute & to command to be obeyed and executed, every one in his owne precinct & power as wel[l] against the Conventicles & prohibited assemblies as against all fugitives & Vagabonds which without foreknowledge and leave of the Governour Generall & Councell & not having performed the Oath of fidelity, in any place shall hide themselves. And if any shall be found to lodge, entertaine, hide or conceale such persons, he shall forfeit for the first time fifty guldens, for the second time twice as much & for the third time four times as much & besides that to be punished arbitrarily. And if any Magistrate, Schout, Marishal or officer shall be found to winke in this case, he shall forfeit the dobble value & declared incapable to serve any more in any publike service.

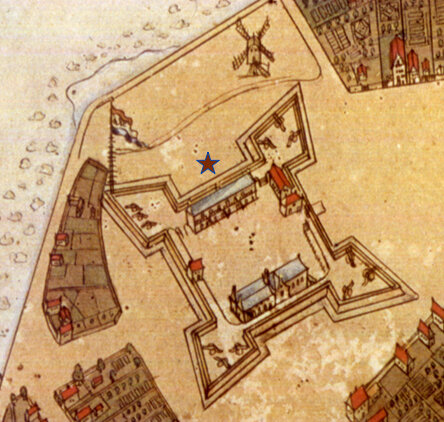

Thus concluded in ye Fort of New Amsterdam in New Netherland the 21 Septr A 1662

Notes on the Text

“their heretofore issued publications”: the 1656 Ordinance against Conventicles and the lost anti-Quaker laws

Conventicles: forbidden or unauthorized religious meetings, held in private or secret settings

barkes: sailing ships, typically with three masts

guldens: Dutch guilders (short for “gulden florins” or “golden florins.”) Roughly equivalent to $6.00 in contemporary money.

shall be found to winke: “connivance,” or turning a blind eye to unorthodox but peaceful worship

“publike”: public

This law supersedes the previous Ordinance against Conventicles passed in 1656, before Quakers had entered New Netherland. The latter was primarily aimed at Lutherans throughout the province, and secondarily at Independents in Middelburgh (Newtown), who began holding meetings after their minister “died of a pestilential disease.” The new law does significantly more than restate the 1656 law as a reminder to the unobservant and disobedient. It rachets up the existing fines, and extends them to more people; it criminalizes distribution of unauthorized religious writings; and it requires all visitors to the colony to register with the authorities and swear a loyalty oath within six weeks of arrival, or be subject to anti-vagrancy laws. These measures mark an escalation on the part of Director-General and Council in their struggle against religious pluralism in the province, particularly Quaker activity. Taken together, they significantly expand the restraints on the liberties of the colonists and the level of intrusion on private activity.

The 1656 ordinance imposed a flat fine of 25 pounds Flanders upon “everyone, whether man or woman, married or unmarried, caught in such meetings,” and a 100 pound fine upon any “unqualified” person officiating, “whether Preacher, Reader, or Singer.” The 1662 edict doubles the previous fine for the first offense, doubles it again for the second offense, and quadruples it for the third- an eight-fold enhancement- and threatens additional, unspecified “arbitrary punishment.” This could include anything from corporal punishment to confiscation of property, imprisonment, or banishment. It also expands liability to the owner of any property where conventicles are held, whether or not they attend the service, and provides for children to be fined as well as “men and women.”

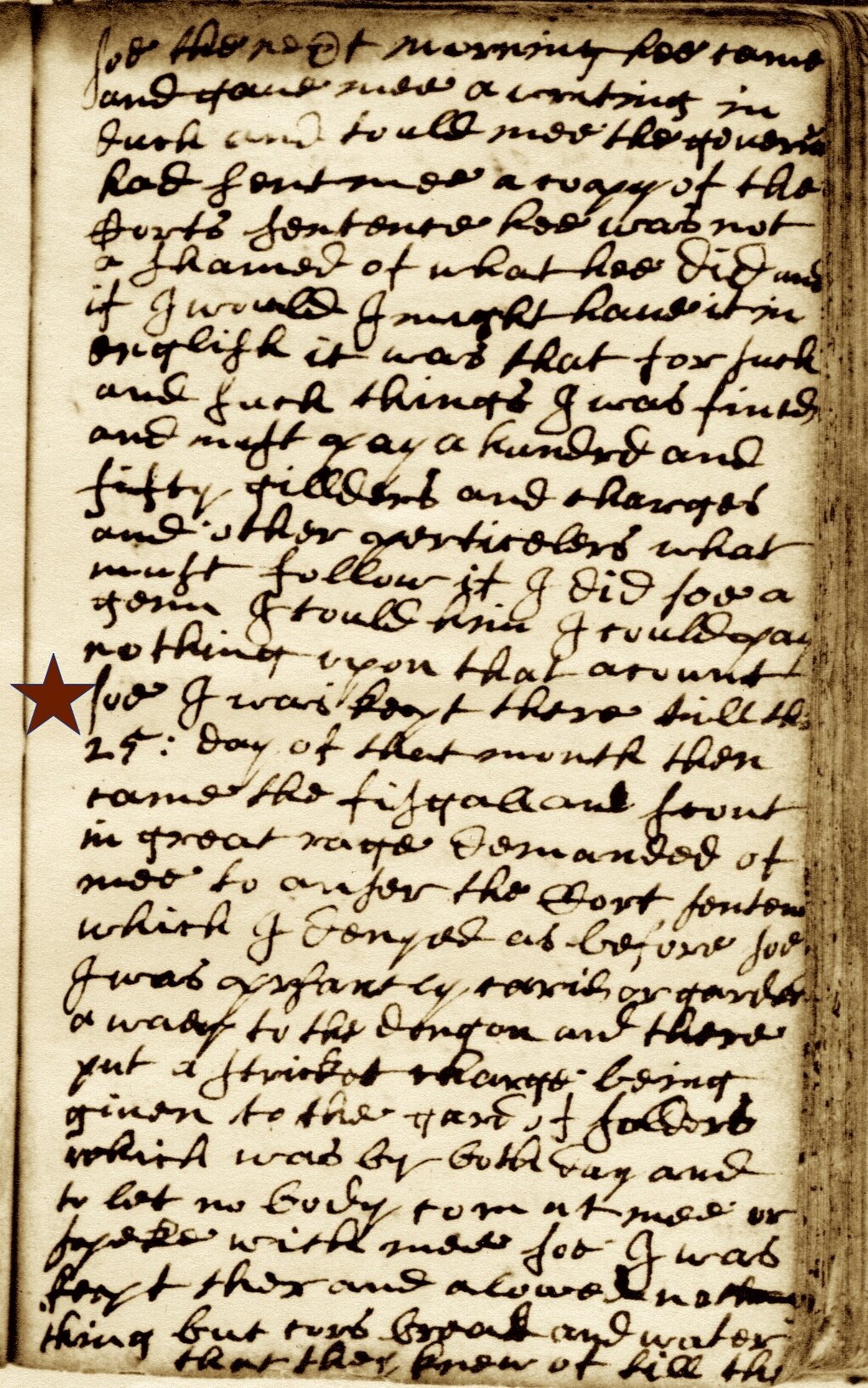

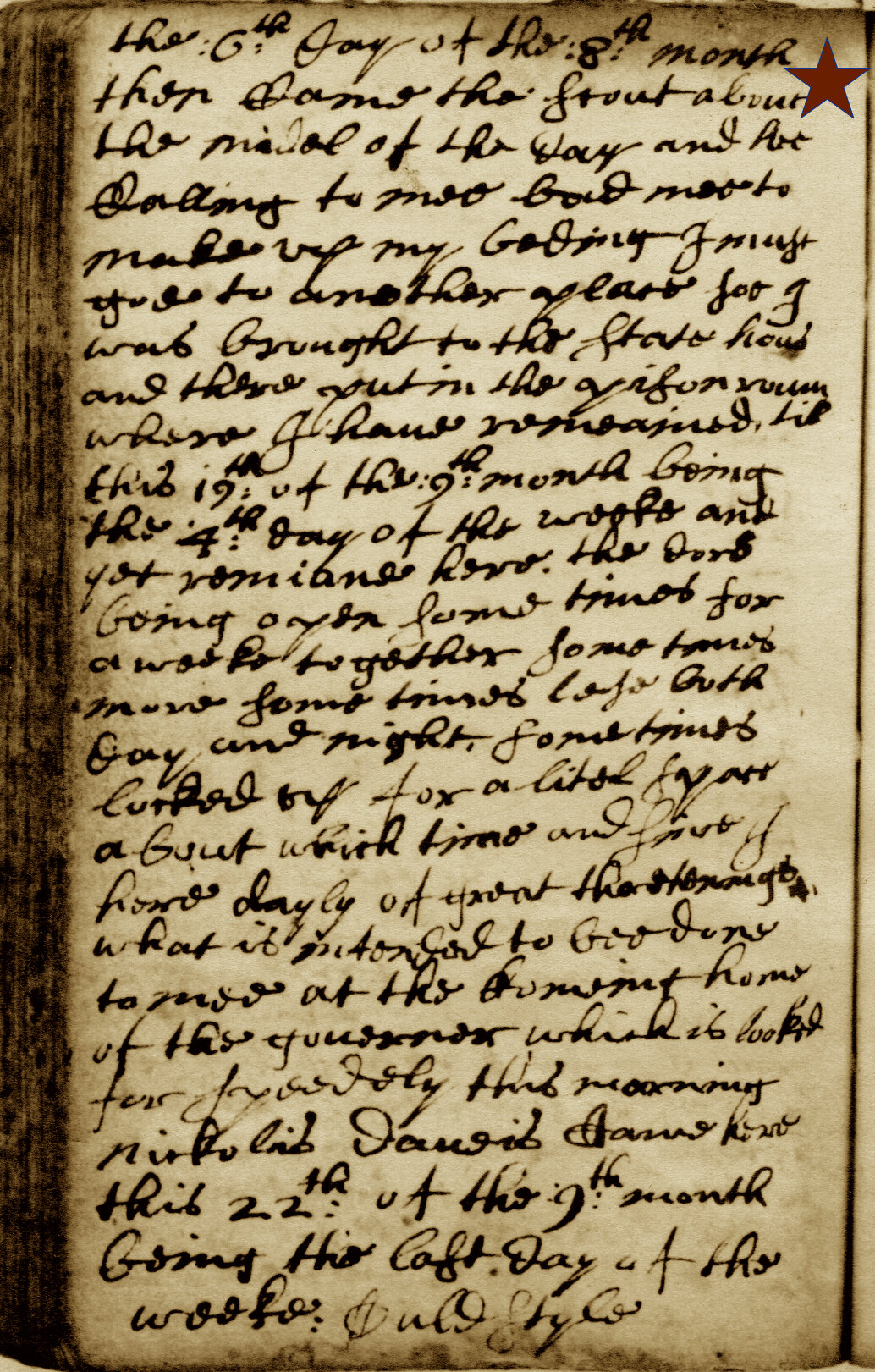

The second article of the 1662 ordinance bans “seditious and erroneous” literature, whether published or unpublished, not excepting works distributed for private consumption rather than liturgical use. It does not define the terms “seditious and erroneous,” although the language of the 1656 ordinance probably applies: “differing from the customary and not only lawful but scripturally founded and ordained meetings of the Reformed divine service, as observed and enforced according to the Synod of Dordrecht in this country…” This provision may have been prompted by reports that Michelle Spicer, one of the Quakers arrested in the same sweep as John Bowne, had distributed tracts in Gravesend. John Bowne himself probably smuggled Quaker literature into the province- oblique references in letters he sent his wife from exile hint that he was also shipping contraband books back to New Netherland, and given his occupation as a trader he may have distributed them earlier. In the English period, Bowne openly acted as the local agent of the Quaker publisher William Bradford.

Finally, the third provision of the Ordinance, requiring all persons in the province to register in person with the Provincial Secretary, and to take a loyalty oath within six weeks of arrival, was clearly a broadside against Quakers in particular. Quakers’ interpretation of Scripture forbade them from swearing oaths, which they interpreted as a violation of Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount:

“But I say unto you, Swear not at all;

neither by heaven; for it is God's throne” – Matthew 5:34 (King James Bible)

This constraint kept early Friends from holding public office, as they could not be sworn in. (In the 1680s John Bowne was actually elected to the New York Provincial Assembly, but had to surrender his seat as he could not take the required oath. In the English period, many Quakers resettled in the new Colony of New Jersey, which had more lenient policies and allowed them to substitute an “affirmation” for an oath.) The Act also subjected legal residents to fines- on the same schedule as those for attending Meetings- for “lodging” or “entertaining” visitors who had not registered and sworn the oath. Faced with the threat Stuyvesant perceived from “heretics, seducers, and deceivers,” the laws were moving away from a simple ban on conventicles, and expanding to encompass a whole penumbra of expression and association surrounding them.

As with the arrest warrant for Bowne and his counterparts issued on September 9th, the local authorities are tasked with enforcement, with the drastic threat of removal from public office if they “winke.” “Winking,” or “turning a blind eye” in the English idiom, was a pragmatic Dutch tradition for dealing with peaceful and otherwise law-abiding sectarians without actually condoning “heresy.” Known as “connivance,” this approach prevailed in more liberal enclaves like Amsterdam, and allowed for some level of co-existence between the public Church and covert faith communities. But New Amsterdam was not old Amsterdam, and Director Stuyvesant was a more militant model than some Directors of the West India Company. In fact, the Directors had even rebuked him for passing the 1656 edict without their knowledge, and particularly for arresting several Lutherans (including a minister) under its auspices.

These were not the only departures from the previous version of the Ordinance. The edict of 1656 offered assurances that it “did not intend any constraint of conscience in violation of previously granted patents.” Notably, the Act of 1662 omits any such reassurances. Stuyvesant had already seen the Patent of Flushing, with its “liberty of conscience” guarantee, thrown in his face by the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance, whereby the inhabitants proclaimed themselves exempt from his Quaker bans by virtue of their Charter. To the contrary, Stuyvesant would go on to pass still more restrictive regulations against Quakers and anyone in their sphere of influence.

SOURCES:

“Ordinance Against Conventicles, September 21, 1662.” [N.Y. Col. MSS. X. 221] pp.428-30 in Laws and Ordinances of New Netherland, 1638-1674, ed. & trans. by E.B. O’Callaghan (Albany : Weed, Parsons, & Co., 1868.) Available from Haithi Trust.

Translation, Ordinance Against Conventicles, February 1, 1656: Gehring, C., trans./ed., New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch, Vol. 6, Council Minutes, 1655-1656 (Syracuse: 1995). A complete copy of this publication is available on the New Netherland Institute website.

“Chapter 2: Connivance,” pp.34-81 in New Netherland and the Dutch Origins of American Religious Freedom, by Evan Haefeli. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

“William Bradford's Book Trade and John Bowne, Long Island Quaker, as his Book Agent, 1686-1691,” by Gerald D. MacDonald. Offprint, pp.209-222 from Essays Honoring Lawrence C. Wroth (Portland: The Anthoensen Press, 1951).